The Water You Trust

When you can't verify everything, verify what matters.

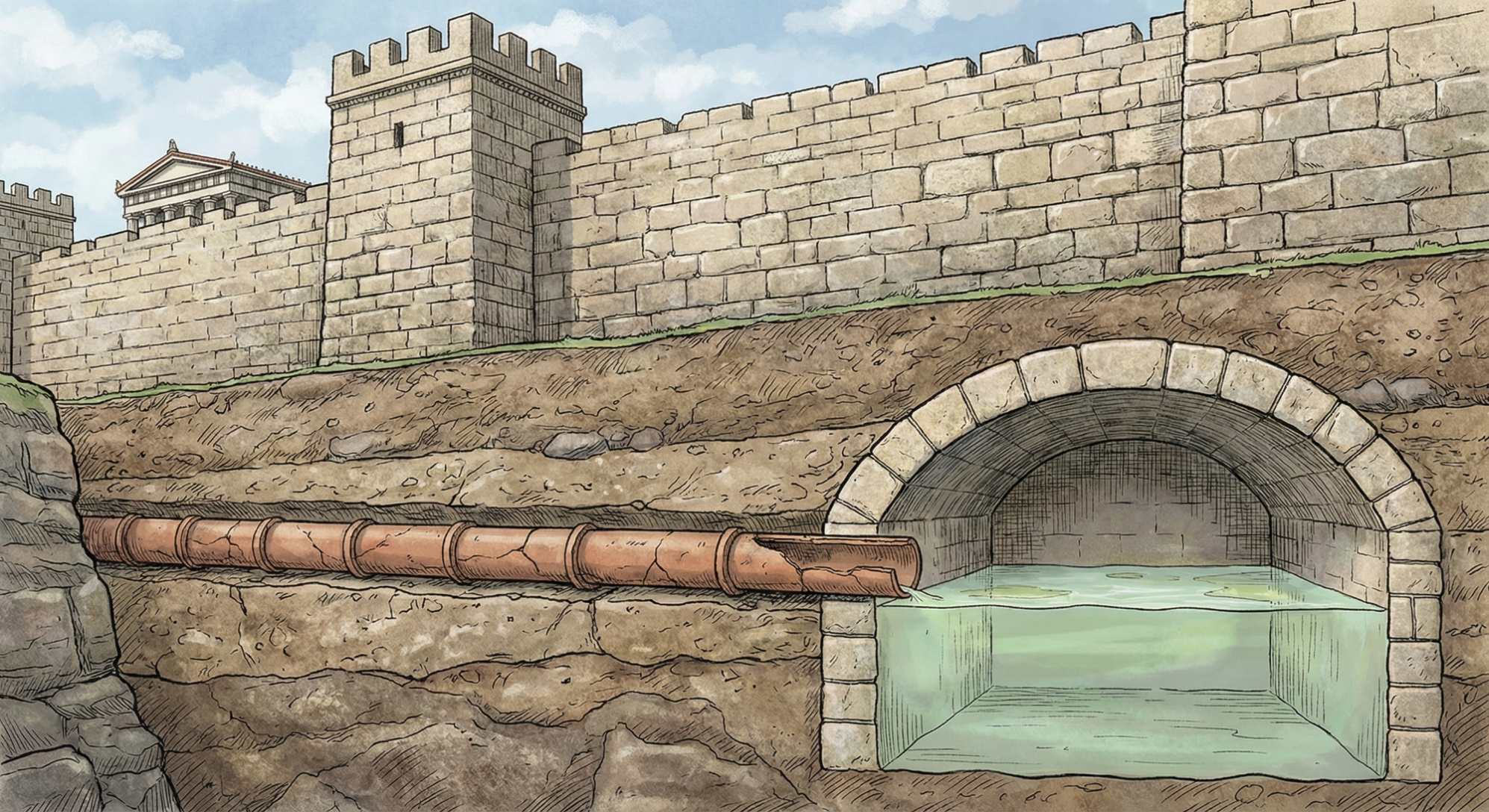

The Siege of Kirrha

In 595 BCE, a coalition of Greek city-states laid siege to Kirrha, a city that controlled access to the sacred Oracle at Delphi. The city walls were strong. Direct assault was failing. The siege dragged on.

Then the attackers discovered something: a water pipe leading into the city.

They stopped attacking the walls. Instead, they poisoned the water supply with hellebore, a toxic plant that causes severe gastrointestinal distress. The defenders, trusting their water—a vital dependency they never thought to question—drank it and were incapacitated. The city fell easily.

Twenty-six centuries later, we build digital fortresses with the same blind spot.

The Fortress That Wasn't

Consider a modern enterprise that has done its homework. Zero-trust architecture. Network segmentation. Next-generation firewalls with behavioral analysis. Maybe even Automated Moving Target Defense or ephemeral compute at the edge. The walls are strong.

None of it is designed to stop poison that's already inside the water.

A supply chain attack doesn't breach your walls. It arrives through your trusted channels: your dependencies, your build tools, your update mechanisms. It's already authenticated. It's already inside the trust boundary. A well-implemented zero-trust architecture does limit the blast radius. Least privilege and microsegmentation constrain what a compromised component can reach. But within the application boundary, the poisoned dependency runs with whatever permissions the host process has. Zero trust narrows the damage; it doesn't prevent the initial compromise.

A supply chain attack doesn't breach your walls. It arrives through your trusted channels: your dependencies, your build tools, your update mechanisms. It's already authenticated. It's already inside the trust boundary. Your zero-trust architecture trusts it implicitly, because you told it to.

The asymmetry is simple: defenders secure the walls; attackers find the pipes.

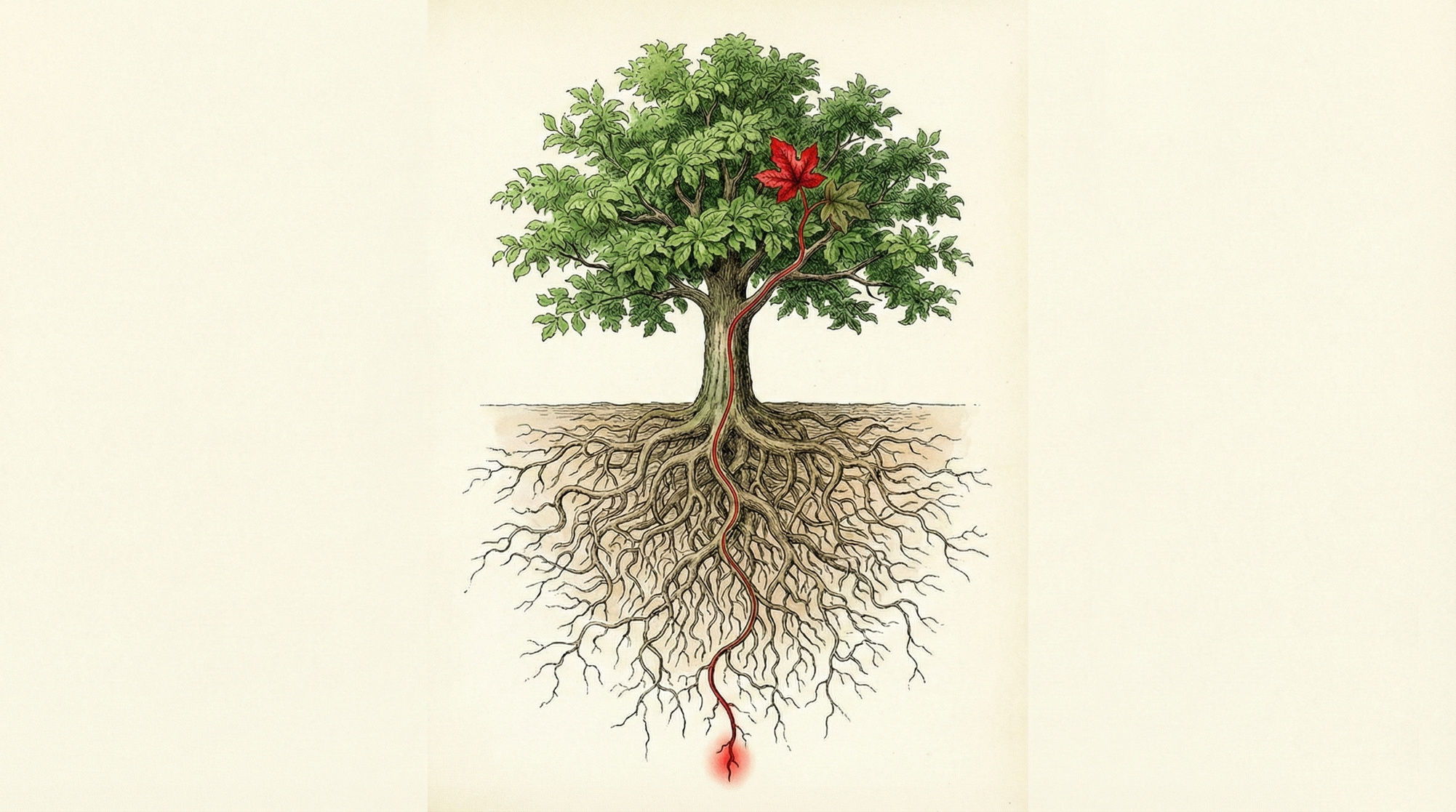

The Dependency Graph You Don't See

Modern software doesn't exist in isolation. It exists as a node in a vast, directed graph of dependencies. Consider a typical AI agent built on a popular framework:

Your AI Agent

└── LangChain

└── Pydantic

└── Typing-Extensions

└── ...

Your agent depends on LangChain. LangChain depends on Pydantic. Pydantic depends on Typing-Extensions. And Typing-Extensions depends on... you probably don't know. Neither do most developers who import it.

This is a fourth-level transitive dependency. If a maintainer of Typing-Extensions has their GitHub credentials compromised, or is coerced, or simply makes a mistake, they can inject code that will execute in your production environment. Your CI/CD pipeline will pull it automatically. Your tests might pass—malicious code can be designed to activate only under specific conditions.

A 2022 Synopsys audit found the average JavaScript project pulls in over 1,000 transitive dependencies. Python projects aren't far behind. Each dependency is a node in a graph. Each node represents trust. Each trust relationship is an attack surface.

You didn't choose to trust the maintainer of that fourth-level dependency. You didn't even know they existed. But your system trusts them completely.

The Opacity Problem: Why AI Workloads Are Worse

Traditional software supply chain attacks are dangerous but at least theoretically analyzable: source code can be scanned, binaries disassembled, signatures compared. Obfuscation makes this hard, but not impossible.

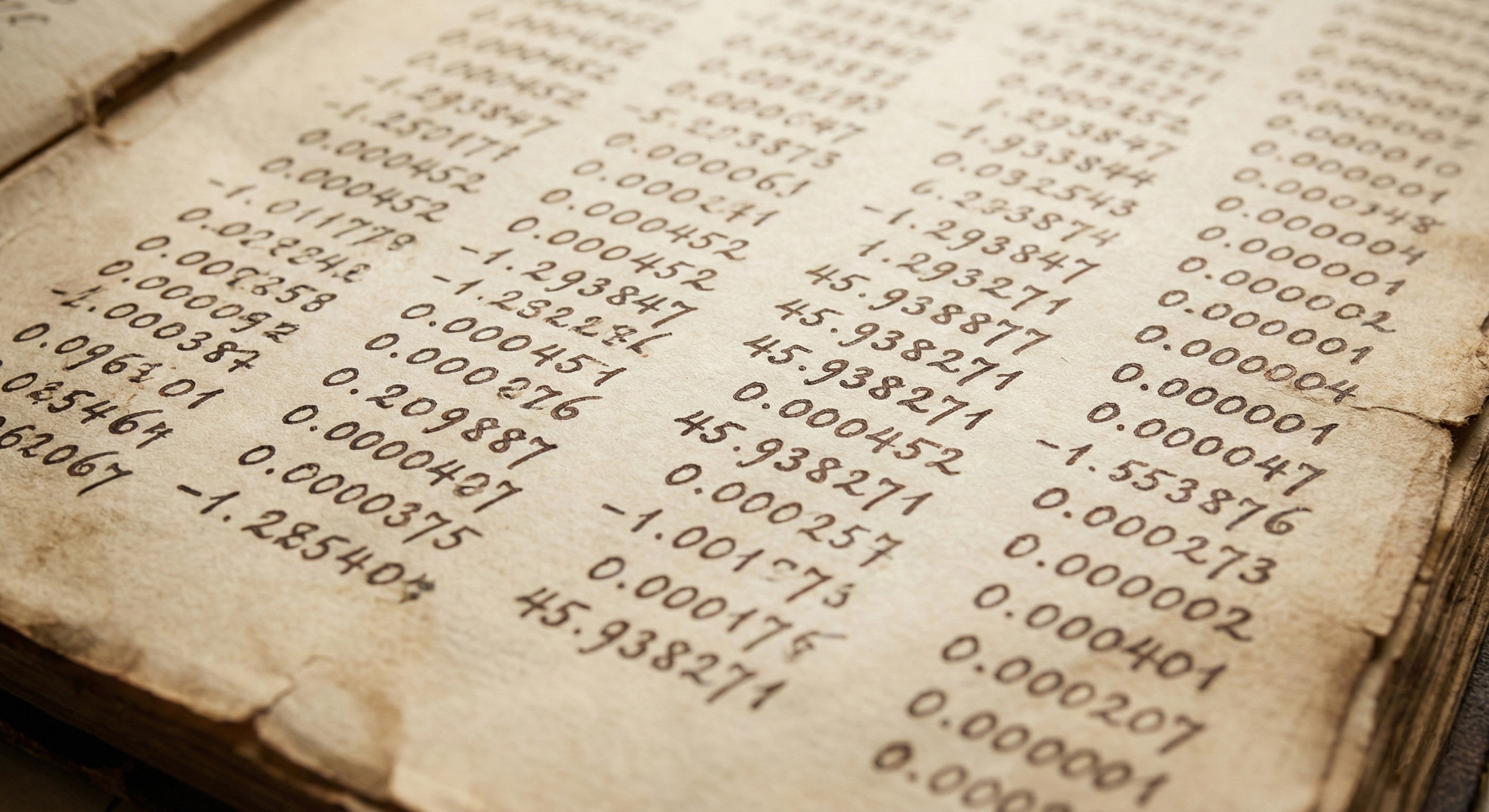

AI models break this assumption entirely.

A 70GB .safetensors or .pickle model file is a vast matrix of floating-point numbers. It is not code in any readable sense. It's a learned function encoded as billions of weights, and you cannot "read" a neural network and determine whether it contains a hidden trigger.

These are called backdoor attacks or trojan models. A model can be trained to behave normally on all standard inputs, but execute specific malicious behavior when it encounters a particular trigger—a specific phrase, image pattern, or data structure. The trigger could be arbitrarily rare, and the behavior could be arbitrarily subtle.

You cannot audit this. Static analysis doesn't apply because the attack surface is in the weights, not the code, and no technique can prove a model is 'clean.'

When you download a pre-trained model from Hugging Face or fine-tune on a third-party dataset, you're trusting the entire provenance chain of that model. Every contributor. Every training run. Every data source. And you have no way to verify what you're trusting.

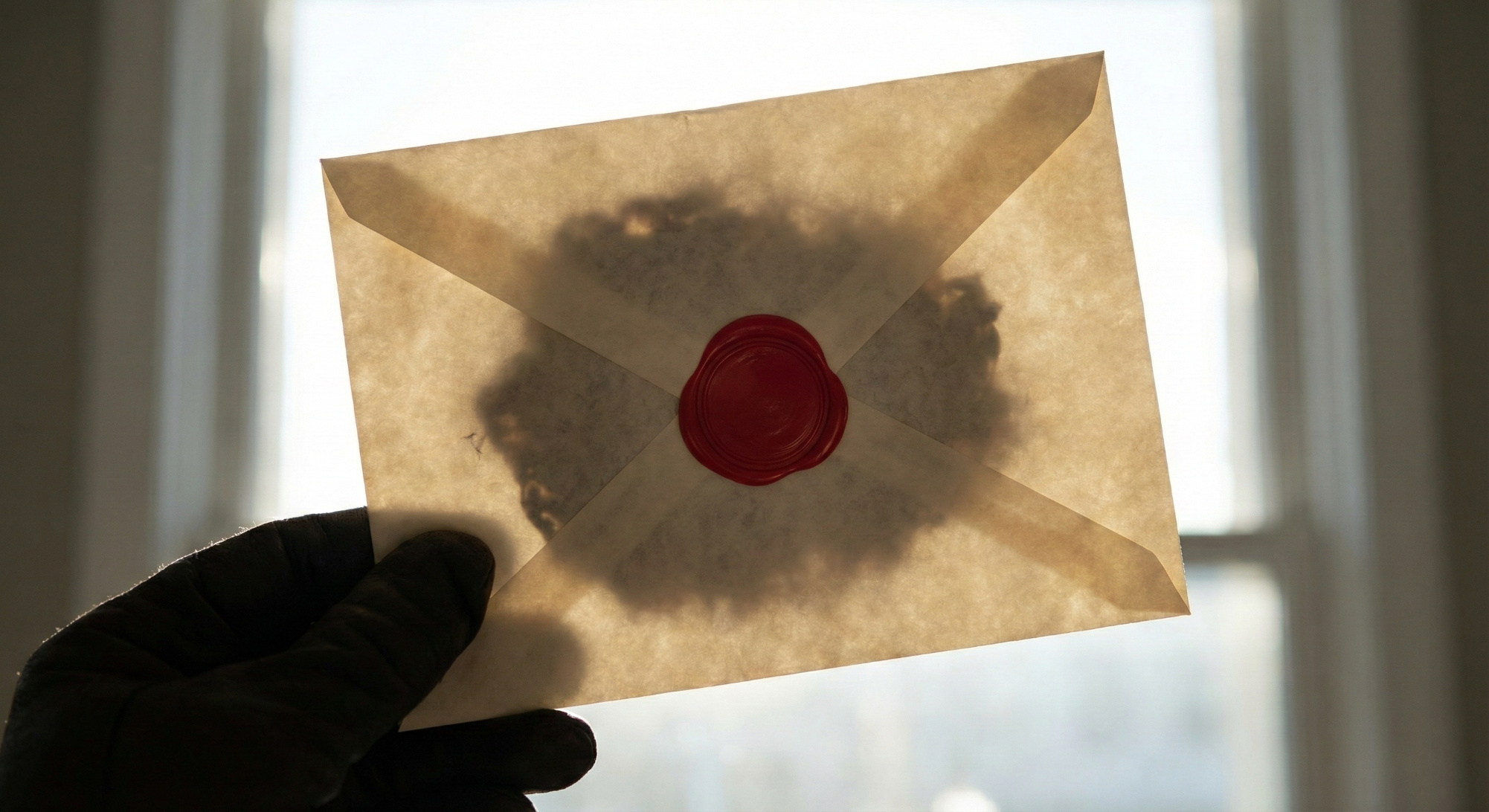

We're Verifying the Envelope, Not the Letter

The security industry has responded to supply chain risks with authentication and provenance tools: Sigstore for cryptographic signing, SPIFFE/SPIRE for workload identity, SLSA for build integrity levels. These are genuinely useful. They're also insufficient.

They prove who, not what.

Sigstore can mathematically prove that "User X signed this artifact at time T." It cannot prove that User X isn't disgruntled, compromised, coerced, or simply having a bad day. The most sophisticated supply chain attacks in history were all properly authenticated. SolarWinds' Orion update was digitally signed by SolarWinds' valid signing key. The authentication was perfect. The payload compromised 18,000 organizations including multiple U.S. government agencies.

SLSA attempts to go deeper: hermetic builds, reproducible artifacts, complete provenance chains. This is the right direction. But consider what 100% assurance would actually require: a complete threat model of every participant in the supply chain. Every developer. Every build system. Every transitive dependency's maintainer. Every credential, machine, and network involved.

That's a graph spanning the world. The personal laptop of a maintainer in Belarus. The home network of a contributor in Argentina. Build systems in data centers you've never heard of. For each node, you'd need to verify not just identity, but intent, operational security, and resistance to coercion.

The graph is too large and too dynamic to ever fully model. Authentication tells you the water came from the official aqueduct. It doesn't tell you the water isn't poisoned.

When technical verification hits a mathematical wall, you have to switch tools. Stop acting like an engineer and start acting like an economist.

The Economics of Depth

So, if we can't verify everything, how do we decide what to verify?

This is an economics question, and one that requires moving beyond the instinct to "minimize risk" toward genuine optimization.

As I've written about in the context of marginal analysis for security decisions, every business decision involves three interconnected forces: Revenue (what we gain), Resources (what we spend), and Risk (what we might lose). You can't optimize one without considering the other two. This is the 3R framework.

Applied to supply chain security:

- Revenue is constrained by how fast you can ship features

- Resources are consumed by verification effort

- Risk is the expected loss from supply chain compromise

The goal is to find the point where the next dollar spent on verification reduces risk by exactly one dollar. Spend less, and you're leaving money on the table. Spend more, and you're wasting resources that could generate revenue.

But supply chain risk is extraordinarily uncertain, and this uncertainty changes everything.

The Uncertainty Problem

In the 3R framework, the optimal spending point is a range, not a single number. Better risk assessment narrows it; worse assessment widens it.

For most security domains, you can tighten this range by mapping your actual system topology: what assets exist, how they connect, what the blast radius of a compromise would be. But supply chain risk resists this approach. To accurately assess a fourth-level transitive dependency, you'd need to know the maintainer's operational security, their susceptibility to coercion, the integrity of their dependencies, and the credential management of everyone with commit access.

Most of this is unobservable. You're not assessing risk. You're guessing.

This creates a very wide optimal range. And when you can't assess likelihood (the probability a dependency gets compromised), pivot to what you can assess: the consequence (what happens if it does). You may not know which pipe will be poisoned, but you can map where each pipe leads and what it touches.

This is the heuristic that makes optimization tractable: distinguish between two different types of supply chain risk, based on their consequences, not their likelihood.

Systemic Risk: Stop Insuring the Hurricane

Why are you spending millions to prevent something that will hurt your competitors just as much as you?

In December 2021, Log4j broke. AWS, Apple, Google, Microsoft, and virtually every enterprise on Earth was vulnerable. This is systemic risk: it affects everyone, which means it has limited competitive impact. When the hurricane hits, the market treats it like a natural disaster, not negligence. Stock prices dip across the sector, but no one gains differential advantage.

Spending millions to deeply verify ubiquitous dependencies yields diminishing returns. You're paying a premium to insure against an event that will devastate your competitors equally.

You don't ignore systemic risk; you shift investment from prevention to detection and recovery. You can't stop the hurricane, but you can have the best early warning system and the fastest recovery time. Monitor for CVE disclosures. Maintain accurate dependency inventories so you know your exposure within hours. Build patching pipelines that can push updates fast. When Log4j hits, the companies that recover in days gain advantage over those who take weeks—even though everyone was equally vulnerable.

Idiosyncratic Risk: When You're Down and They're Not

Now flip the scenario. You get breached through a niche library you imported for a specific feature. The custom model you fine-tuned. The internal build tool three people maintain. Your competitors are unaffected. They're online; you're not. You lose trust, customers, and revenue to them.

This is idiosyncratic risk, risk that's specific to you. And this is where the marginal calculus shifts.

For idiosyncratic dependencies, the next dollar spent on verification might reduce risk by five or ten dollars—you're far from the optimal point. Your limited budget should flow toward these edges of the graph, not the core everyone shares.

Dig deep where you're unique. Stay shallow where you're common.

Your first $100K verifying a niche ML library might eliminate $500K in idiosyncratic risk exposure. That same $100K auditing React or TensorFlow? It might shave a few percentage points off a risk that would hit your competitors equally anyway.

Security friction is a tax on velocity. Every hour spent on verification is an hour not shipping features. The 3R framework makes this tension explicit: Resources consumed by security reduce Revenue capacity.

Require manual audit of every transitive dependency? Your developers stop shipping. Three-week security review for every model import? Your AI features lag behind competitors.

Your competitor who accepts a slightly higher risk profile ships three months before you. They capture the market. You reduced Risk but you also reduced Revenue. The 3R optimization failed—you traded one form of business damage (breach) for another (irrelevance).

The goal is to find the point where the next dollar on verification reduces total risk by exactly one dollar, accounting for direct breach costs, competitive damage, and lost revenue from delayed shipping. Given the massive uncertainty in supply chain risk, you'll be operating within a range rather than hitting a precise point—but knowing the range beats guessing.

Finding Balance in the Graph

So where does this leave us?

Supply chain security cannot be solved with perimeter defenses, because the threat is already inside the trust boundary. Authentication alone won't do it either; signatures prove provenance, not intent. And complete verification is impossible. The graph is too large and too dynamic.

But architecture still matters. It just needs to start from a different assumption: that trusted components will eventually be compromised. An architecture that treats supply chain poisoning as an expected condition can limit what a compromised dependency touches and how fast you recover from it.

Once you accept that assumption, the question shifts from "how do we prevent compromise" to "where do we spend our limited budget." That's a 3R optimization problem across a risk topology. Balance Revenue, Resources, and Risk, and accept that the uncertainty will always be wide:

- Harden your own supply chain first: this is non-negotiable. Your Git repositories, artifact registries, CI/CD pipelines, and signing keys are 100% idiosyncratic risk: if they're compromised, only you suffer. They're also 100% within your control. Unlike third-party dependencies, you can actually verify and harden them. SolarWinds was a build system attack, not a dependency attack. Before optimizing how you consume external code, ensure the infrastructure that builds, signs, and deploys your code isn't the weakest link. The marginal return on investment here is highest. Everything else in this framework assumes it.

- Map your dependency graph, starting with SBOM. You cannot optimize what you cannot see. A Software Bill of Materials is the baseline: an inventory of every component in your software supply chain. This sounds basic, yet a surprising number of organizations can't produce one. Without it, you're optimizing a graph you haven't drawn. Once you have the inventory, classify nodes: which are systemic (shared with the industry) and which are idiosyncratic (unique to you)? That classification drives rational allocation of verification effort.

- Concentrate verification on idiosyncratic risk. The niche libraries. The custom integrations. The unique data pipelines. The marginal value of prevention is highest here, because breaches create differential competitive damage. Prioritize by consequence: the ERP's dependencies before the cafeteria menu's. But no verification is 100%, so layer detection and recovery capabilities as a backstop.

- For systemic risk, invest in detection and recovery, not prevention. Deep verification of Log4j or OpenSSL yields diminishing returns. The risk reduction doesn't justify the resource expenditure when the impact is industry-wide. Instead, invest in CVE monitoring, accurate dependency inventories, and fast patching pipelines. You can't stop the hurricane, but you can recover faster than your competitors.

- Price the innovation tax explicitly. Make the Resources-Revenue tradeoff visible. Every verification step has a cost in shipping velocity. If you can't articulate the risk reduction that justifies that cost, you're engaged in security theater, not optimization.

- For AI workloads, treat model provenance as critical path. The opacity of neural networks makes traditional verification impossible. This shifts the focus to the supply chain of the models themselves: training data provenance, fine-tuning history, and the trustworthiness of model sources. Given the unverifiability, this is often where idiosyncratic risk concentrates.

- Invest in narrowing the uncertainty range. The better you can map your actual dependency topology and assess risk quantitatively, the narrower your optimal spending range becomes. Graph-native threat modeling helps, not by eliminating uncertainty, but by replacing guesswork with structural analysis where possible.

The defenders of Kirrha trusted their water because they had always trusted their water. They never questioned the pipe that sustained them—until it destroyed them.

We build digital fortresses the same way. We trust our dependencies because we must. Modern software is impossible without trust in thousands of unseen contributors. We cannot clean the entire river. We can only filter the cup we're about to drink.

That's not a security decision. It's a business decision, a 3R optimization problem. To solve it, you must distinguish the systemic rivers everyone drinks from the idiosyncratic pipes that feed only you. That distinction is invisible in a spreadsheet; it only appears when you map the topology of trust.

This article was originally published on Medium