Where the Map Ends

A note on the analogy: The Vietnam War caused immense human suffering on all sides. This article examines the strategic and geometric principles at play, not to glorify conflict, but because the lessons about asymmetric warfare translate directly to how we think about defensive security today.

The US military in Vietnam had overwhelming superiority in every measurable category: air power, artillery, personnel, logistics, technology. They controlled the skies. They had satellites. They had the map.

The Củ Chi tunnel network was approximately 250 kilometers of underground passages, built with shovels and baskets. By any resource accounting, it should not have posed a strategic challenge.

Yet it did. The tunnels allowed fighters to appear inside fortified perimeters, strike, and vanish. Air superiority was irrelevant underground. Artillery couldn't hit what couldn't be located. The map was useless because the map only showed the surface.

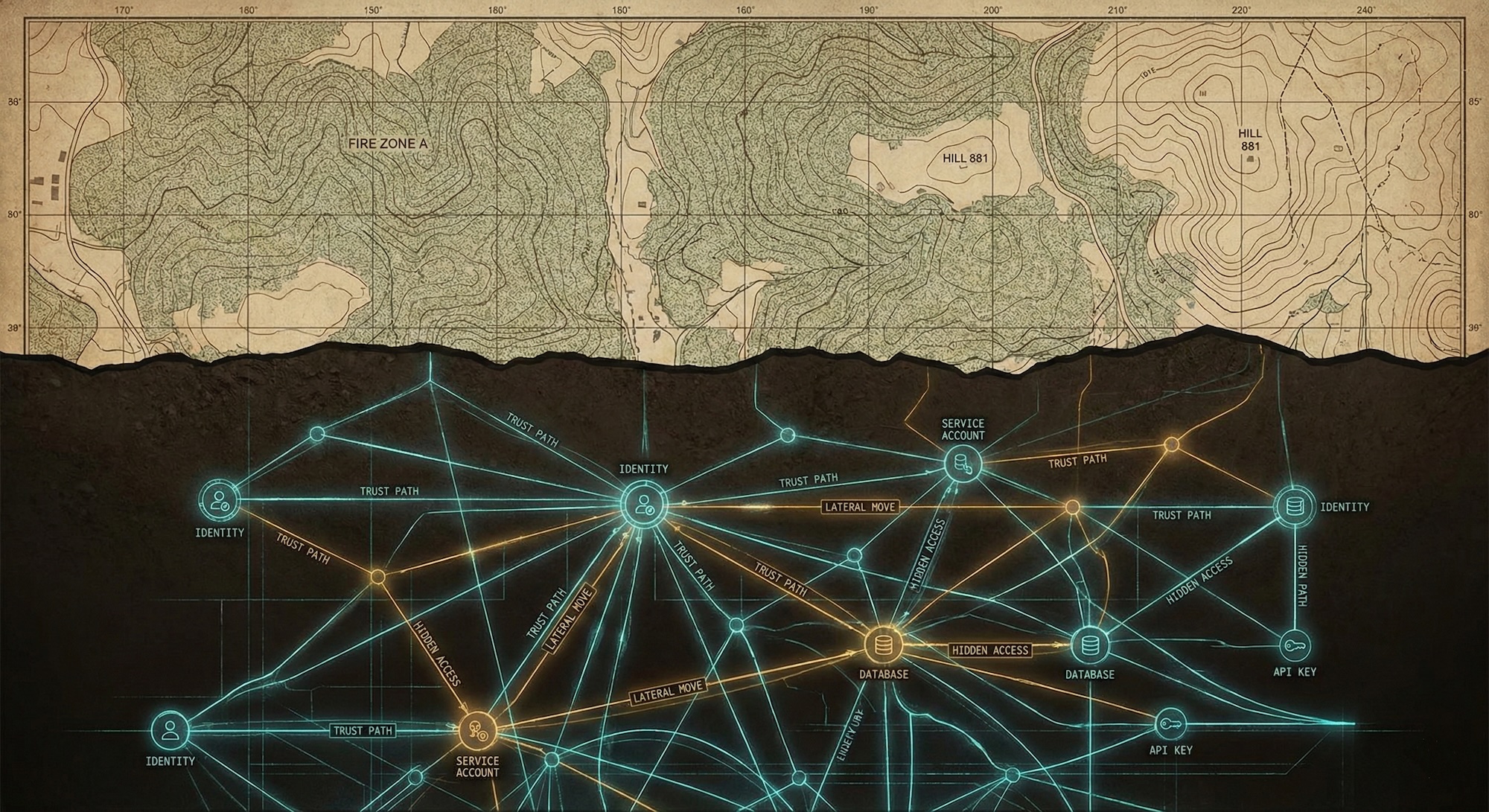

The US forces were fighting a war of topography: hills, fire zones, documented positions. The tunnel builders were fighting a war of topology: connectivity, hidden paths, network resilience.

This distinction matters for cybersecurity because we are currently on the wrong side of it.

The List-Based War

The military measured success with quantifiable outputs: enemy casualties, territory swept, patrols completed. These are list-based metrics. They count items. They don't measure structural relationships.

The tunnel strategy operated on different mathematics entirely. The relevant questions were: Can we connect point A to point B without being observed? If one route is compromised, does an alternative path exist? What is the minimum distance between our network and their high-value targets?

These are graph questions. They concern edges, reachability, and path redundancy.

The asymmetry was not primarily about courage or ideology. It was geometric. One side was optimizing for node elimination (body counts). The other side was optimizing for edge preservation (connectivity). When you destroy nodes in a resilient graph, the graph routes around them. When you preserve edges, you maintain operational capability regardless of individual losses.

Modern security operations make the same mistake.

The Contemporary Version

Nobody defends the "castle-and-moat" approach anymore. The response has been Zero Trust, micro-segmentation, identity-aware access controls.

These are real improvements. Sophisticated implementations do model relationships—identity graphs, device trust chains, behavioral baselines. But most organizations don't get there. They end up implementing Zero Trust as a list-based exercise.

Consider the typical implementation:

- Inventory all users (a list)

- Inventory all applications (a list)

- Define access policies mapping users to applications (a list of pairs)

- Enforce policies at access points (checkpoints)

This is better than a single perimeter. But it still operates on the documented topology. It secures the surface.

The attacker is not constrained to the surface.

When a threat actor compromises an identity, they inherit that identity's graph position. They don't care about your application inventory. They care about: What service accounts does this application use? What databases do those accounts access? What other systems trust those databases? What credentials are cached on those systems?

These questions trace paths through a graph that your access policy spreadsheet does not contain. The attacker is in the tunnels. Your checkpoints are above ground.

The Hidden Graph

Every organization has two architectures: the one that was designed, and the one that actually exists.

The designed architecture appears in network diagrams, access control matrices, compliance docs.

The actual architecture includes:

- Service accounts with permissions granted "temporarily" years ago

- Trust relationships between systems established for a migration that completed in 2019

- API keys embedded in configuration files that no one remembers creating

- Network paths that exist because a firewall rule was never removed

- Identity federation chains that create transitive trust across security boundaries

- Identity tokens that allow traversing from a developer laptop to a production database via the cloud control plane, bypassing the network firewall entirely

This is the tunnel network. It exists. It is traversable. It does not appear on the map.

When we say "the attacker moves laterally," we mean they're walking through tunnels our visibility tools don't show. They're exploiting edges in the actual graph, not the documented one.

The Economics of Asymmetry

The economics explain why this asymmetry persists.

Defense:

Security budgets fund tools that operate on lists: asset inventories, vulnerability scanners, log aggregators, endpoint agents. These tools are expensive. They require licensing, integration, staffing, and maintenance.

They produce more lists. Vulnerabilities to patch, alerts to triage, compliance gaps to close. The queue never empties.

Each item on each list consumes resources. The marginal cost of processing the 10,000th alert is similar to processing the 1st. Scale does not help; it multiplies the problem.

Offense:

An attacker needs one viable path. Not a complete map. Not every vulnerability. One sequence of edges from their entry point to your valuable assets.

Their resource expenditure is proportional to path discovery, not comprehensive coverage. They can ignore 99% of your infrastructure if the 1% they need is traversable.

This is the tunnel economics. Dig where it matters. Ignore the rest.

The gap:

We spend resources enumerating and monitoring surfaces. Attackers spend resources discovering and traversing graphs. Our tool categories—SIEM, EDR, CSPM, CNAPP—are built for surface visibility. Graph traversal capability exists, but it's rarely central to security operations.

The US military had functionally unlimited resources compared to tunnel construction costs. Irrelevant—because those resources went to surface control while the adversary operated underground.

Same with security budgets. The advantage disappears if the money flows to list-processing while adversaries navigate graphs.

The Tunnel Rat Problem

The only effective counter to the tunnel network was direct engagement: soldiers who entered the tunnels and fought in the graph, node by node. This was dangerous, slow, and required entirely different skills than surface warfare.

The security equivalent is threat hunting. The real kind—not triaging alerts or processing vulnerability reports, but actually investigating graph relationships. Why does this identity have a path to that system? What would an attacker do from this position? Which edges shouldn't exist?

This is resource-intensive. It requires analysts who think in graphs, not checklists, and tooling that models relationships, not inventories.

Most security teams can't sustain it. The list-processing workload consumes all available capacity. The tunnel rat function is either absent or permanently understaffed.

Mapping the Subsurface

So how do you get tunnel rat capability when you can't staff tunnel rats?

You make the graph visible. Instead of asking analysts to manually reconstruct attack paths every time, you give them tooling that models the actual architecture. The work shifts from "discover the tunnels" to "decide which tunnels matter."

Accept that two architectures exist. Your documentation describes one. Reality contains another. Until you model the actual graph, your security controls address a system that does not quite exist.

Shift observability from nodes to edges. Asset inventory answers "What do we have?" Identity inventory answers "Who are our users?" Neither answers "What can reach what, and how?" Graph databases model relationships as first-class entities—which makes reachability a question you can actually ask.

Prioritize by risk, not by count. Some edges connect low-value nodes through paths that never reach critical assets. Others provide one-hop access to crown jewels. The question is: What's the risk reduction per dollar spent removing this edge versus that one? The graph structure tells you which edges matter. Without the graph, you're guessing.

Collapse unnecessary tunnels. Unused permissions nobody remembers granting. Trust relationships left over from a 2019 migration. Service accounts with admin rights to half your infrastructure. These serve no business purpose but remain traversable. Find them. Remove them. That's structural risk reduction, not just policy enforcement.

The Geometric Lesson

The tunnel network succeeded not because of superior resources, but because it operated on a different geometric plane. Topography (the surface) was contested. Topology (the connections) was not.

Modern attackers don't compete with our surface tools. They navigate edges we haven't mapped.

We can keep increasing security budgets, deploying more list-processing tools, hiring more analysts to triage alerts. Or we can acknowledge that the fight is happening in the graph—and that controlling connectivity matters more than controlling territory.

Until we model the actual graph of trust and access in our environments, we're deploying artillery against an enemy who isn't on the surface.

The graph exists. It's discoverable. The tunnels can be mapped before someone else walks through them.

This article originally published on Medium.