What the Fall of Thermopylae Teaches Us About Network Security

The most famous last stand in history wasn't defeated by superior force. It was defeated by a goat path.

In 480 BC, King Leonidas of Sparta executed one of history's most elegant defensive strategies. With 300 Spartans and a few thousand Greek allies, he held the pass at Thermopylae against Xerxes' army of over 100,000 Persians.

For two days, it worked perfectly.

Then a local Greek named Ephialtes revealed a hidden mountain path—the Anopaia—that bypassed the Hot Gates entirely. The Persians poured through. The Spartans were surrounded. The battle was over.

We have spent two thousand years admiring Leonidas' courage. Security professionals should be studying his topology.

The Perfect Vertex Cut

Leonidas chose Thermopylae for its geometry, not its symbolism.

In graph theory, a vertex cut is a set of nodes that, when removed, disconnects two parts of a graph. The Hot Gates were a natural vertex cut—a narrow pass between mountains and sea that forced all traffic through a single point.

The network looked like this:

[Persia] -----> [Hot Gates] -----> [Greece]

Source Chokepoint Destination

By controlling the chokepoint, Leonidas transformed the problem. Persian numerical superiority became irrelevant. In the narrow pass, only a handful of soldiers could engage at once. The massive Persian "flow" was throttled to a trickle.

In cybersecurity terms, Leonidas built the ultimate perimeter firewall. All traffic forced through a single inspection point. Superior technology (Spartan training, bronze armor) concentrated at the chokepoint. Everything outside the perimeter was hostile; everything inside was protected.

For 48 hours, this architecture held against the largest army the ancient world had ever assembled.

Then the topology changed.

The Edge That Wasn't on the Map

Ephialtes was a local farmer who knew the mountains. He knew something the Spartans either didn't know or chose to ignore: the Anopaia path, a goat trail through the peaks that emerged behind the Greek lines.

In graph theory terms, Ephialtes revealed a hidden edge:

[Persia] -----> [Hot Gates] -----> [Greece]

| ↑

+-------> [Anopaia Path] ---------+

(Hidden Edge)

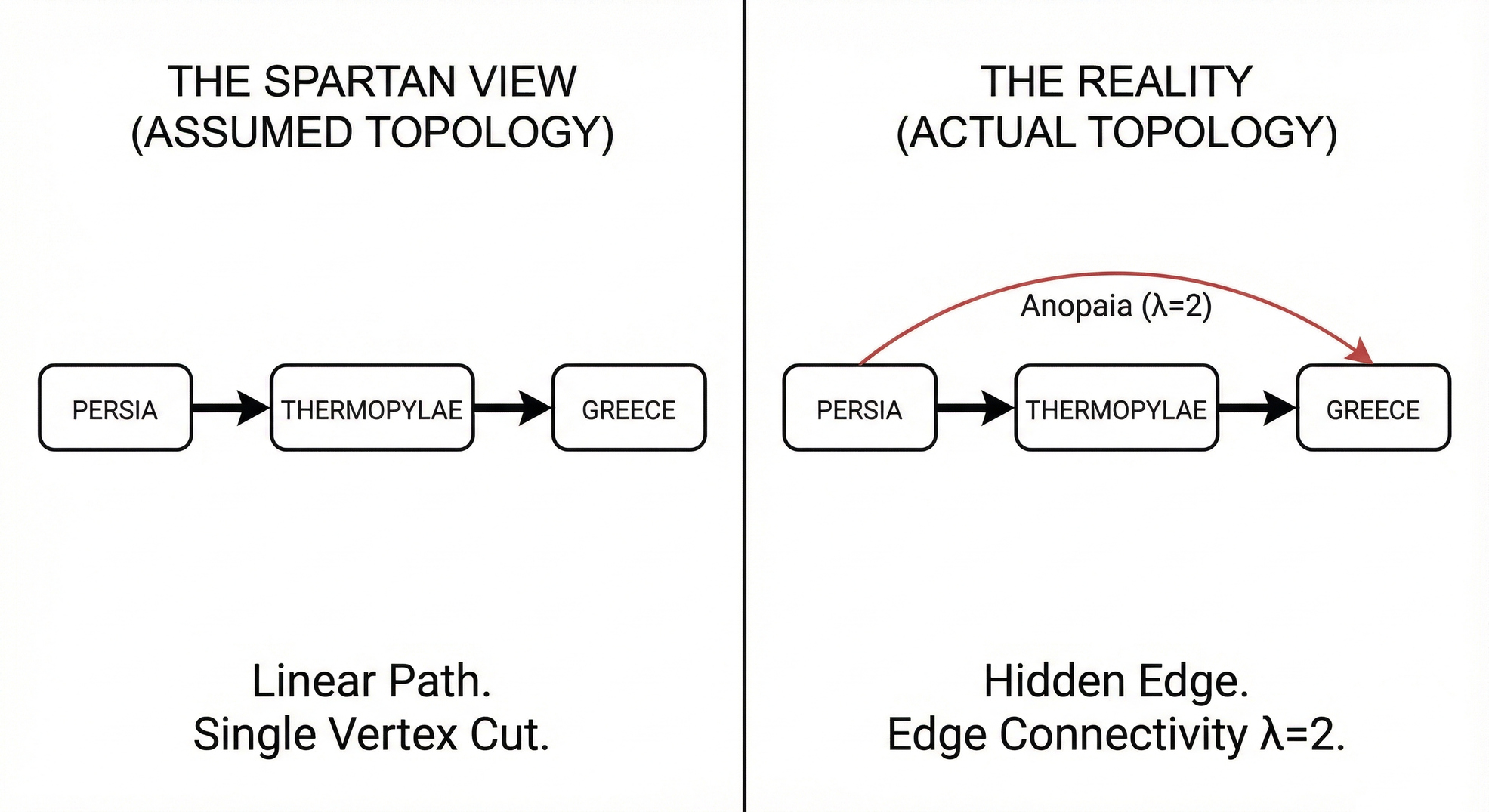

The Spartans' security model assumed a specific topology: one path, one chokepoint, total control. The real topology included an edge they hadn't accounted for.

Once the Persians traversed that edge, the entire defensive architecture collapsed. The Hot Gates went from an impenetrable fortress to a death trap. The Spartans weren't just bypassed—they were surrounded.

This is the core lesson: Security based on controlling a chokepoint is only as good as your knowledge of the topology.

The Spartans failed because they assumed that the network had only one path, not because their chokepoint was weak.

The Mathematics of Betrayal

Let's formalize why chokepoint security is mathematically fragile.

Edge Connectivity (λ)

In graph theory, the edge connectivity of a graph is the minimum number of edges you must remove to disconnect it. If the attacker only needs one path to win, and you only block one path, you are betting your survival that the graph's connectivity is exactly 1.

You are betting there is no λ=2.

The Anopaia path proved λ=2. One hidden edge, and the entire strategy collapsed.

The Max-Flow Min-Cut Theorem

The fundamental theorem of network flow states: the maximum flow from source to destination equals the capacity of the minimum cut.

Leonidas tried to create a min-cut with capacity approaching zero—force all Persian flow through a bottleneck where it could be destroyed. Mathematically sound, if you've correctly identified the min-cut.

But the Anopaia path meant the actual min-cut wasn't just the Hot Gates. It was:

Min-Cut = {Hot Gates, Anopaia Path}

Leonidas secured half the min-cut. Half isn't enough.

The Connectivity Problem

The mathematical truth that kills chokepoint strategies is:

You cannot prove a network is secure by securing only the edges you see. You must account for edges you don't see.

The Spartans mapped the visible topology. The Persians, with local intelligence, mapped the actual topology. The gap between those maps was fatal.

The Modern Thermopylae: The Chokepoint Fallacy

We could think of Thermopylae as an analogy for the network perimeter. But the math of the Hot Gates applies to every boundary in your architecture.

Whether it's your perimeter firewall, a segmentation gateway between IT and OT, or a Zero Trust policy enforcement point between two cloud VPCs—the logic is identical. You are establishing a chokepoint to control flow between two zones.

And in every case, you are making the same dangerous assumption Leonidas made: that the chokepoint you control is the only path that exists.

You assume the Edge Connectivity (λ) between Zone A and Zone B is exactly 1 (the firewall). But in complex networks, connectivity is rarely that clean.

The Modern Anopaia Paths:

| Ancient | Modern Equivalent |

|---|---|

| Goat path through mountains | Dual-homed server bridging "Prod" and "Dev" VLANs |

| Local farmer's knowledge | Developer hardcoding an IP address to bypass DNS |

| Mountain terrain assumed impassable | "Air-gapped" backup server connected to a management LAN |

| Trusted Greek ally | Shared service account with access to both segments |

| Ephialtes (the traitor) | Disgruntled insider or compromised admin credentials |

| Ephialtes' knowledge | A legacy router with a "temporary" any/any rule |

| Supplies from allied merchants | Compromised software dependency (supply chain attack) |

The Persian army didn't break through the Hot Gates. They walked around them. Attackers do the same to your internal boundaries:

- The Jump Box Bypass: You place a strict firewall between Corporate and Production. But a "jump box" exists that has interfaces in both. If an attacker compromises the jump box, the firewall is mathematically irrelevant.

- The Backup Loop: Your sensitive database is segmented. But it backs up to a server that is also accessible from the general office network. The backup path becomes the attack path.

- The Cloud Peering: You secure the front door of your VPC, but a forgotten VPC Peering connection allows traffic from a forgotten test environment.

- The Trusted Package: Your firewall inspects all traffic. But the compromised npm package or SolarWinds update walks through the front door with a valid signature. The chokepoint welcomes it in.

Every firewall is a Thermopylae. And if you haven't mapped the topology, every Thermopylae has a goat path.

The Fractal Failure: Why Segmentation Often Fails

When the Persians emerged from the Anopaia path, the problem wasn't just that they bypassed the gate. It was that the Greeks had no Plan B for a topology change.

Modern networks suffer from this recursively.

We criticize "flat networks," but even segmented networks often fail because the segmentation relies on imperfect topological knowledge. Organizations implement "Zero Trust" by placing firewalls between internal zones, believing they have stopped lateral movement.

They haven't. They've just created smaller Thermopylaes.

If you implement micro-segmentation but miss a hidden dependency (a hardcoded API call, a shared hypervisor management port), you haven't secured the segment. You've just created a more expensive illusion of control.

In graph terms:

Zone A → [Internal Firewall] → Zone B

| ↑

+-----> [Hidden Edge] ---------+

(Shared Admin Workstation)

The attacker doesn't attack the firewall. They compromise the Shared Admin Workstation (the hidden edge) and "walk" into Zone B.

The "distance" between your most secure asset and your least secure asset is often much shorter than your network diagram suggests. The diagram shows a fortress with multiple gates. The graph shows a mesh of shortcuts.

This is why "dwell time"—the time attackers spend inside before detection—remains high even in segmented networks. The attackers are finding edges the defenders simply denied existed.

What Leonidas Should Have Done

Let's rewrite history with graph theory.

1. Map the Topology AND Assess Edge Criticality

To his credit, Leonidas knew the Anopaia path existed—Herodotus records that he stationed the Phocians to guard it. But knowing an edge exists isn't the same as understanding its strategic value.

The Anopaia path was narrow and difficult. It looked like a minor edge. But in graph terms, it had the same impact on the min-cut as the Hot Gates. Traversing either meant game over. Leonidas treated a critical edge as a secondary concern.

In modern terms: graph-native threat modeling. Don't just inventory your connections—analyze their criticality. A "minor" admin path to your database has the same cut value as your main API if both lead to the crown jewels. Query the actual topology, then rank edges by impact, not by appearance.

2. Assume Your Controls Will Fail

The Phocians were the control on the Anopaia path. When the Persians arrived at dawn, they heard the enemy coming—and retreated to a nearby hilltop, assuming they were the target. The Persians simply ignored them and walked past.

The guards saw the threat. They misinterpreted the signal. The breach occurred anyway.

In modern terms: assume breach. Your controls will fail—through misconfiguration, alert fatigue, or simple human error. Design your architecture assuming the perimeter will be bypassed. Because it will be.

3. Defense in Depth

The Spartans committed everything to the chokepoint. When it was bypassed, there was no fallback.

In modern terms: micro-segmentation. Don't create a hard shell around a soft interior. Create multiple defensive boundaries. If one chokepoint falls, the attacker should face another, then another.

4. Reduce Edge Connectivity

If Leonidas had fortified the Anopaia exit as heavily as the Hot Gates, the min-cut would have held. Two chokepoints are harder to bypass than one.

In modern terms: Zero Trust architecture. Every connection requires verification. No implicit trust based on network location. The attacker who bypasses the perimeter should find not a flat network, but a graph where every edge requires authentication.

5. If You Can't Block, You Must Watch

The 3R reality is that Leonidas couldn't clone 300 Spartans to fortify every mountain path. He had finite Resources. Modern CISOs face the same constraint—you cannot put an expensive next-gen firewall on every internal segment.

In graph terms, an edge's danger isn't defined by its physical size, but by its impact on the cut. The narrow Anopaia path had the same strategic value as the main gate—traversing either meant game over.

The Phocians were supposed to be a sensor on that path. They failed because they were passive and misread the signal. When the Persians arrived, they assumed they were the target and retreated. The Persians walked past. Alert fatigue. False negative. Breach.

In modern terms: continuous monitoring (NDR). If you cannot afford to block an edge—due to cost, latency, or business continuity—you must monitor it with extreme prejudice. When a low-privileged "goat path" account suddenly accesses a critical asset, you don't need a wall. You need an immediate alarm that doesn't get ignored.

The Phocians had the right idea. They just needed better detection logic—and the authority to act.

The Graph Theory of Resilient Defense

The mathematical principle that Thermopylae teaches is

Security ≠ Strength of the Chokepoint

Security = Topology of the Network

You can build the strongest firewall in the world. If an attacker can route around it, its strength is irrelevant.

Resilient defense requires:

- Complete Topology Mapping

You cannot secure edges you don't know exist. Graph databases let you model actual connectivity—not assumed connectivity—and query for paths you didn't expect. - High Edge Connectivity

Don't rely on single chokepoints. Design architectures where attackers must traverse multiple controlled edges to reach critical assets. Make the min-cut expensive. - Continuous Topology Validation

Networks change. New edges appear. Old edges persist past their purpose. Regular graph analysis finds the Anopaia paths before attackers do. - Path-Based Security Thinking

Instead of asking, “Is this chokepoint secure?”, ask, “What paths exist to critical assets, and are they all controlled?”

The Bottom Line

Thermopylae wasn't a failure of courage or capability. It was a failure of topology.

The Spartans built the perfect vertex cut—and were destroyed by an edge they didn't account for. Their security model assumed they knew the network. They didn't.

Modern security architecture makes the same mistake. We build elaborate firewalls—at the edge and internally—and assume that controlling the obvious paths is sufficient. Meanwhile, attackers find the goat trails: phishing, compromised credentials, supply chain attacks, cloud misconfigurations.

The lesson from Thermopylae isn't "build stronger walls." It's "know your graph."

Because somewhere in your network, there's an Ephialtes edge. A path that exists but isn't documented. A connection that bypasses your chokepoint entirely.

The Persians found theirs in three days.

Your attackers have automated scripts running 24/7. They might have found yours three days ago.

The Spartans assumed they knew the topology. They were wrong. Graph-native security platforms map your actual network—not your assumed network—and find the Ephialtes edges before attackers do.

Historical Note: The fate of Ephialtes remains disputed. Some sources say he was killed years later for an unrelated crime; others suggest he lived in exile. Herodotus records that the Greeks put a price on his head. His name, in modern Greek, has become synonymous with "nightmare"—a fitting legacy for the man who proved that topology defeats tactics.

-- This article originally published on Medium.