From Risk Owners to Responsible Parties

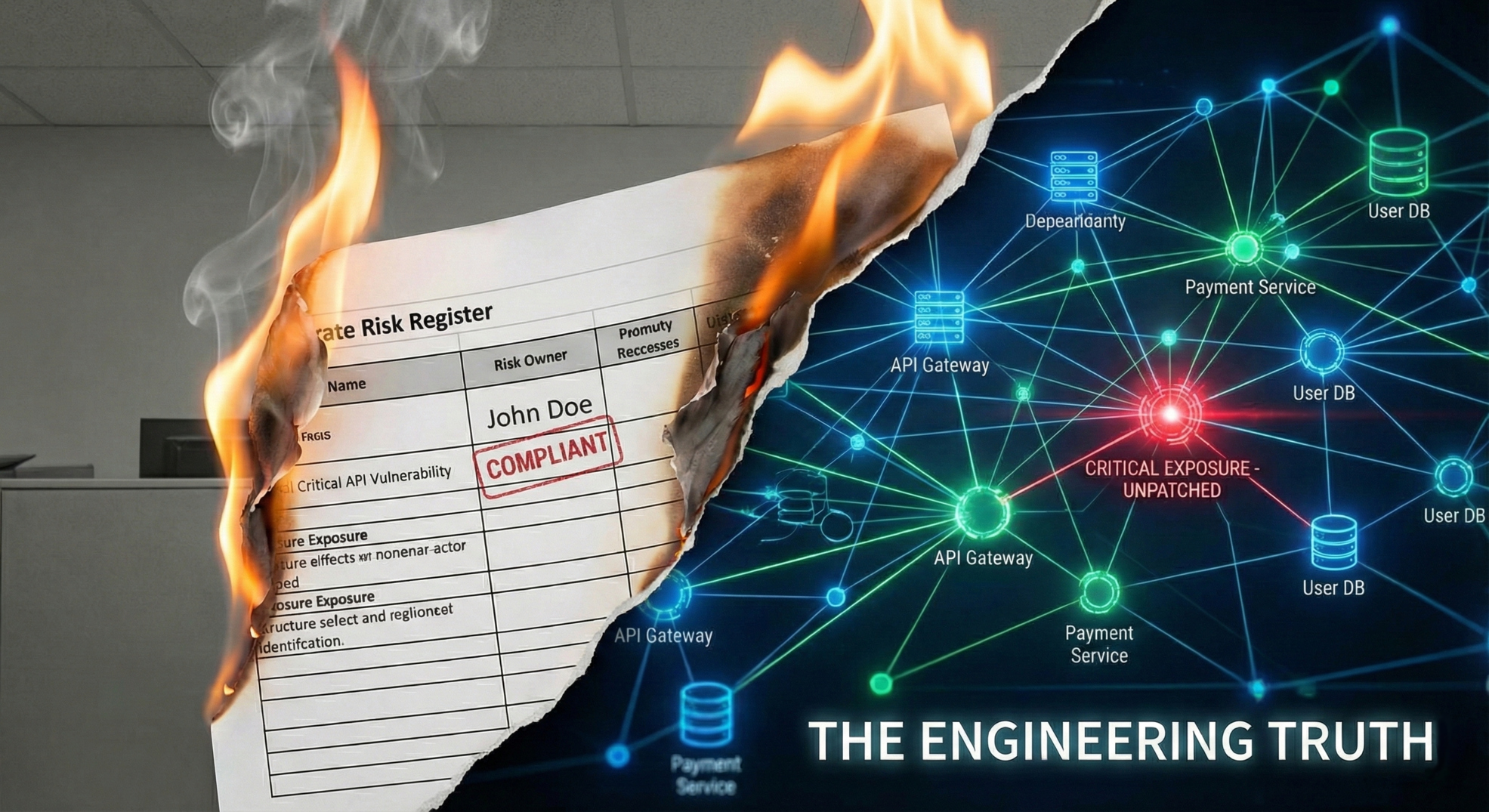

Your security team just finished a comprehensive risk assessment. You've identified 47 risks, classified them by severity, and assigned an "owner" to each one. The spreadsheet looks professional. The board presentation went well.

Three months later, nothing has changed. The risks are still there. The "owners" haven't done anything about them.

From Organizational Logic to Personal Stakes

In the previous articles, we established that organizations must balance Revenue, Resources, and Risk rather than falling for binary traps. But mathematical optimization is useless without human execution.

This is where "Risk Ownership" fails. It treats risk as a static variable in a spreadsheet, ignoring the human element entirely.

To turn the 3R model from a theory into a reality, we need to move beyond passive labels. We need a mechanism that stops treating risk as "documentation" and starts treating it as an incentive.

This article explores why "Ownership" creates paperwork while "Responsibility" creates action—and how to use technology to assign it objectively.

The Problem with "Risk Ownership"

"Risk owner" sounds like a real role. Organizations assign risk owners. Frameworks require risk owners. Audit committees ask "who owns this risk?"

But in practice, "Risk Ownership" is often just a label in a spreadsheet. And labels don't fix vulnerabilities.

The fundamental failure is one of incentives. When you assign someone as a "risk owner" without giving them the corresponding authority or accountability, you are offering them a terrible economic trade:

- You ask for Resources: "Spend your time and political capital fixing this."

- You offer zero Revenue: "You will get no credit because preventing a disaster is invisible."

- You create zero personal Risk: "If it blows up, you can honestly say you didn't have the budget or authority to stop it."

Under these conditions, the rational choice for any risk owner is to do nothing. They will acknowledge the risk, update the date on the register, and go back to their "real" job—the one that actually affects their career.

"Risk ownership" is passive. It is administrative. It allows an organization to feel covered ("We have a name next to the risk!") while the underlying danger remains exactly the same.

What Actually Drives Action is Responsibility

There is a crucial difference between "owning" a risk and being responsible for it. Ownership is a status; Responsibility is a burden.

Risk Ownership asks: "Are you aware of this?" Responsibility asks: "Are you willing to answer for the outcome?"

To move from passive awareness to active mitigation, you must assign Responsibility, which consists of three non-negotiable elements. If any one of them is missing, action stops:

- Authority (The Power to Spend Resources): The responsible party must have the power to make decisions, allocate budget, or change workflows. Without authority, they are just observers

- Accountability (The Personal Risk): There must be clear, personal consequences for the outcome. Success brings reward; failure brings scrutiny. This turns the organizational risk into a personal stake.

- Capability (The Ability to Execute): They must have the tools, data, and skills to act. Without capability, accountability is just cruelty.

When you assign "Risk Ownership" without these three elements, you are creating the illusion of control. You have a name in a cell, but no engine to drive the fix.

Compare the difference:

- Risk ownership: "IT Security owns the risk of unpatched systems."

- Reality: IT Security doesn't control when application owners schedule maintenance windows, doesn't control the budget for automation tools, and can't force compliance.

or

- Responsibility: "John (Application Team Lead) is responsible for ensuring his team's systems are patched within 30 days of critical vulnerability disclosure. IT Security provides scanning and remediation tools. Unpatched systems trigger escalation to his VP."

- Reality: Clear authority (John controls his team's maintenance windows), clear accountability (John's performance tied to this metric, escalation goes to his VP), clear capability (tools provided).

The second version drives action. The first version drives spreadsheet updates.

Responsibility is Personal

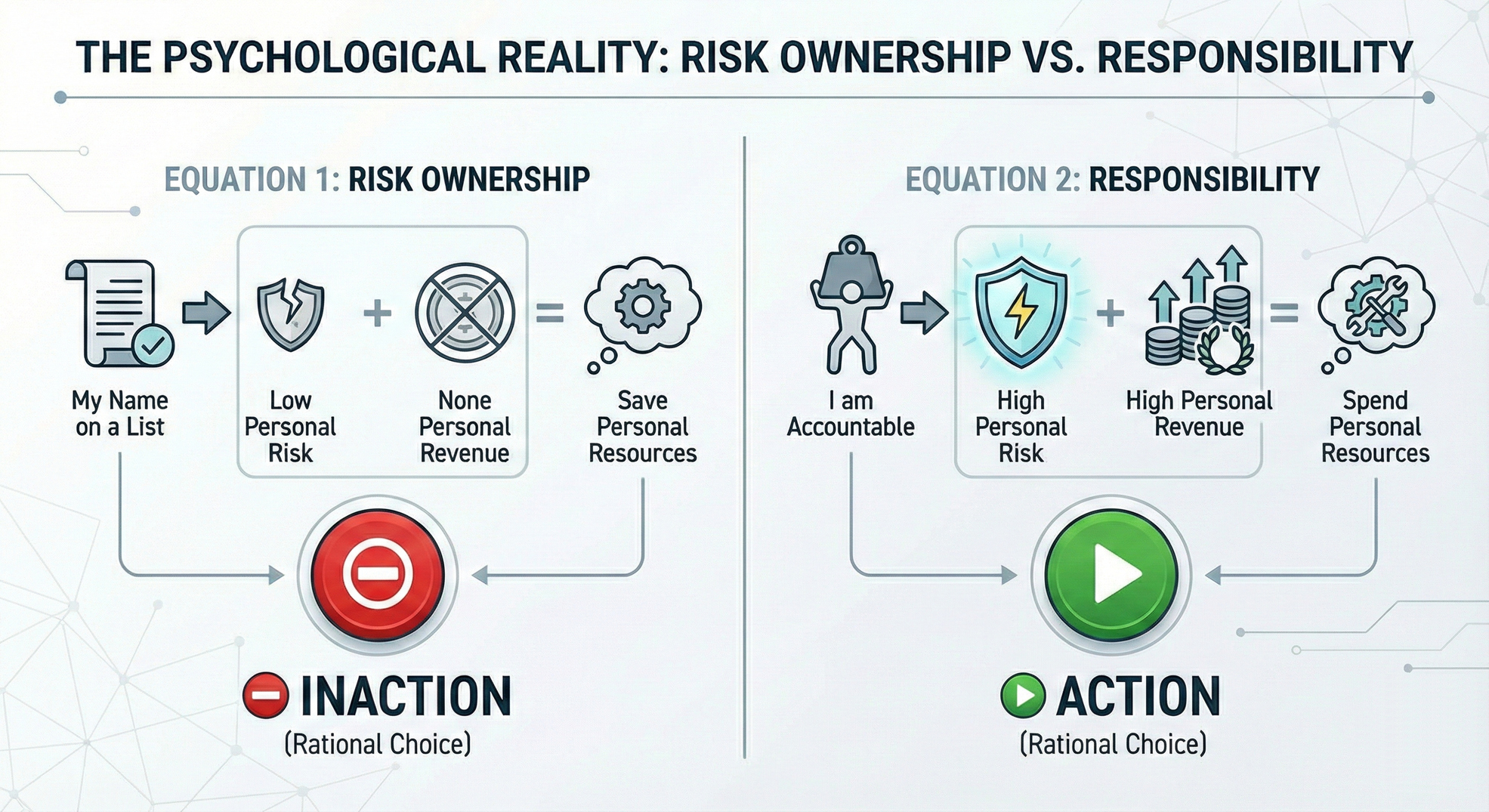

When you make someone truly responsible for a risk, you aren't just changing the org chart—you are changing their internal economic calculation.

Every employee, whether they realize it or not, runs their own personal version of the 3R model:

- Personal Revenue (Upside): Career advancement, bonuses, recognition, reputation.

- Personal Resources (Cost): Time, attention, political capital, stress.

- Personal Risk (Downside): Blame, scrutiny, embarrassment, career damage.

Most "Risk Ownership" fails because it ignores this internal P&L. It asks people to spend Resources (time/effort) without offering Revenue (reward) or creating Risk (consequences). The rational move is inaction.

Responsibility changes the math.

When you make someone responsible—with authority and accountability—you force a new calculation:

- The "Risk Owner" Scenario (Passive):

- Calculation: "My name is on a list. If this breaks, I can blame the lack of budget."

- Personal Risk: Low.

- Personal Revenue: None

- Incentive: Save Personal Resources. Do nothing.

- The "Responsible Leader" Scenario (Active):

- Calculation: "I am accountable for this outcome. If it breaks, it's on me."

- Personal Risk: High.

- Personal Revenue: High (Trust, Reputation, Career Growth).

- Incentive: Spend Personal Resources to mitigate Risk and capture the Upside. Take action

This is why responsibility drives action: it aligns the Organizational Risk with the Personal Risk. It ensures that the employee optimizes for the company's safety because their own success depends on it.

The Power of the Question

Even when the structural elements are the same—same decision, same authority, same resources—the specific language you use changes the outcome.

Compare these two interactions:

- Interaction A (The Compliance Check): "You are listed as the risk owner for this system. Please update the register."

- Response: "Sure." (Nodding, passive acceptance).

- Result: Documentation.

- Interaction B (The Responsibility Check): "We are deciding to accept this risk. Can you take full responsibility for that decision?"

- Response: ... (Silence/Hesitation).

- Result: Calculation.

That moment of silence is crucial. It is the sound of the employee running their Internal 3R calculation. They are asking themselves: "If I say yes, and this blows up, can I survive the consequences? Do I actually have the control I need to prevent it?"

The question acts as a forcing function.

You cannot just nod at "Can you take responsibility?" It demands a binary answer.

- If the answer is "Yes": You have genuine commitment. They have accepted the personal risk and are now motivated to mitigate it.

- If the answer is "No": You have uncovered a critical gap. They are admitting they lack the Authority or Capability to handle the Accountability.

"Risk Ownership" allows for ambiguity. It allows people to hide. "Responsibility" forces a decision: either commit to the outcome or admit you can't handle it. Both answers are valuable data; silence and "sort of" are not.

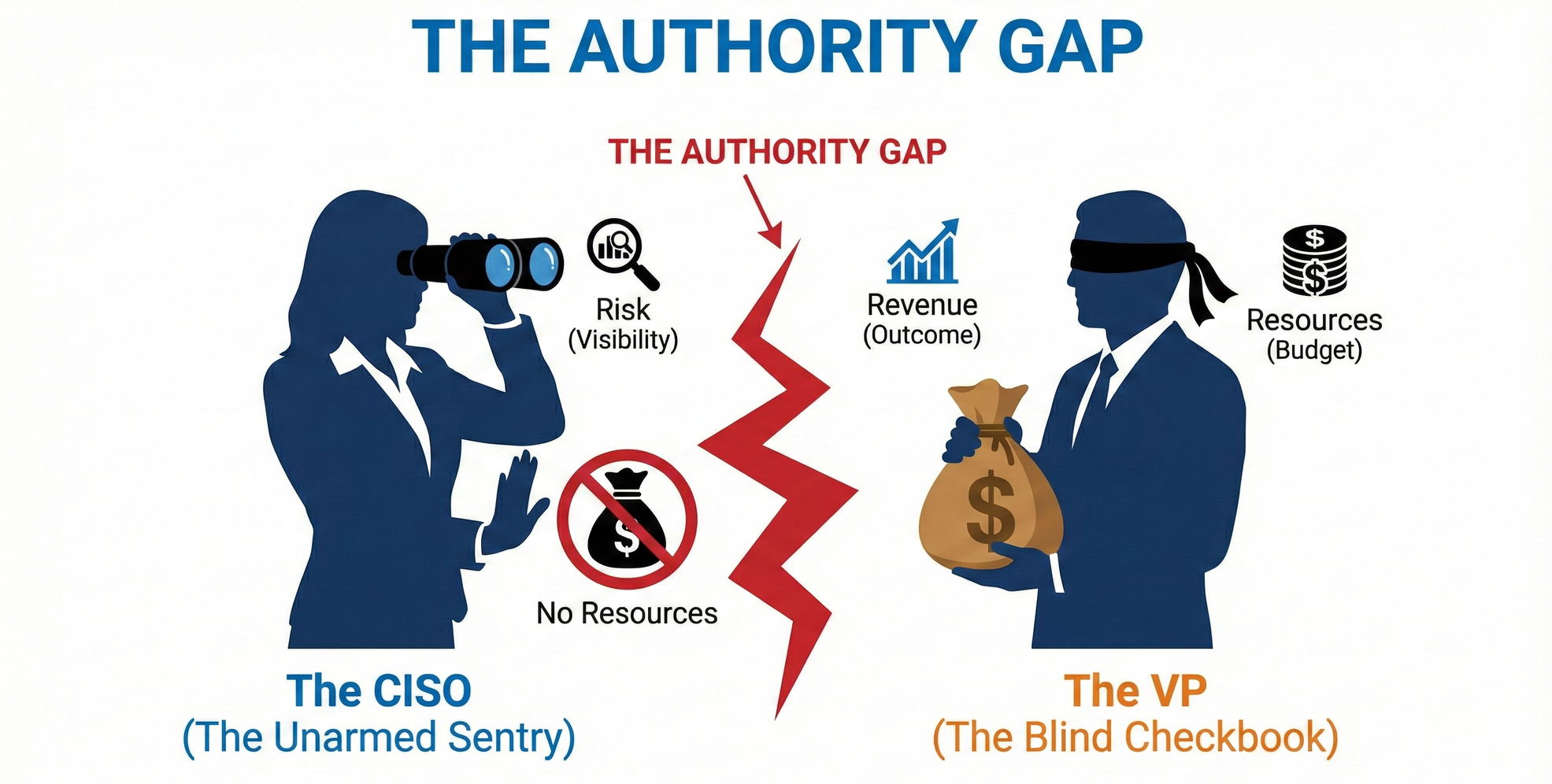

The Enterprise Reality is Fragmented Authority

In an ideal world, one person would have the visibility to see the Risk, the authority to allocate the Resources, and the incentive to protect the Revenue.

In the real world, these three elements are shattered across the org chart. This creates the Authority Gap—the space where responsibility goes to die.

We typically see four specific fractures where the 3R model breaks down:

- The "Unarmed Sentry" (Responsibility without Resources)

- Who: The CISO or Risk Manager.

- The Break: They are the watchtower. They see the threats clearly (Risk), but they do not control the engineering backlogs, the product roadmaps, or the headcount (Resources).

- Result: They have the vision but not the weapons. They can only "advise," not decide, leaving them to own the anxiety without the lever to relieve it.

- The "Blind Checkbook" (Resources without Visibility)

- Who: The Product VP or Business Unit Leader.

- The Break: They control the budget and timelines (Resources/Revenue). However, they lack the technical visibility to understand how their "fast and cheap" decisions are creating technical debt (Risk).

- Result: They optimize for features because the risk is invisible to them—until it explodes.

- The "Silo Trap" (Fragmented Scope)

- Who: Application Teams vs. Infrastructure Teams.

- The Break: Team A owns the App. Team B owns the Cloud. The attacker exploits the seam between them.

- Result: Both teams honestly say "My part is secure," yet the system is vulnerable. No one has the authority to secure the gap.

- The "Veto Trap" (Negative Authority)

- Who: Compliance or "Gatekeeper" Security Teams.

- The Break: They lack the resources to fix the problem and the authority to change the product, but they possess the "Negative Authority" to stop the deployment.

- The Friction: They exercise this veto without owning the business consequences (Revenue/Resources). They can stop the launch, but they don't lose their bonus if the product misses the market window.

- Result: The business views Security as an obstruction, not a partner. This leads to "Executive Override"—where a VP "accepts the risk" just to bypass the gatekeeper, often without understanding the technical reality. The veto creates a bypass, not safety.

The Consequence: Political Deflection

When authority is fragmented, "Risk Ownership" becomes a game of hot potato. Stronger stakeholders deflect responsibility to weaker ones.

- The VP says: "Security signed off on this." (Ignoring that Security had no veto power).

- Security says: "The Business accepted the risk." (Ignoring that the Business didn't understand it).

This is why spreadsheets fail. You cannot assign "ownership" to a gap. You must use data to find the bridge.

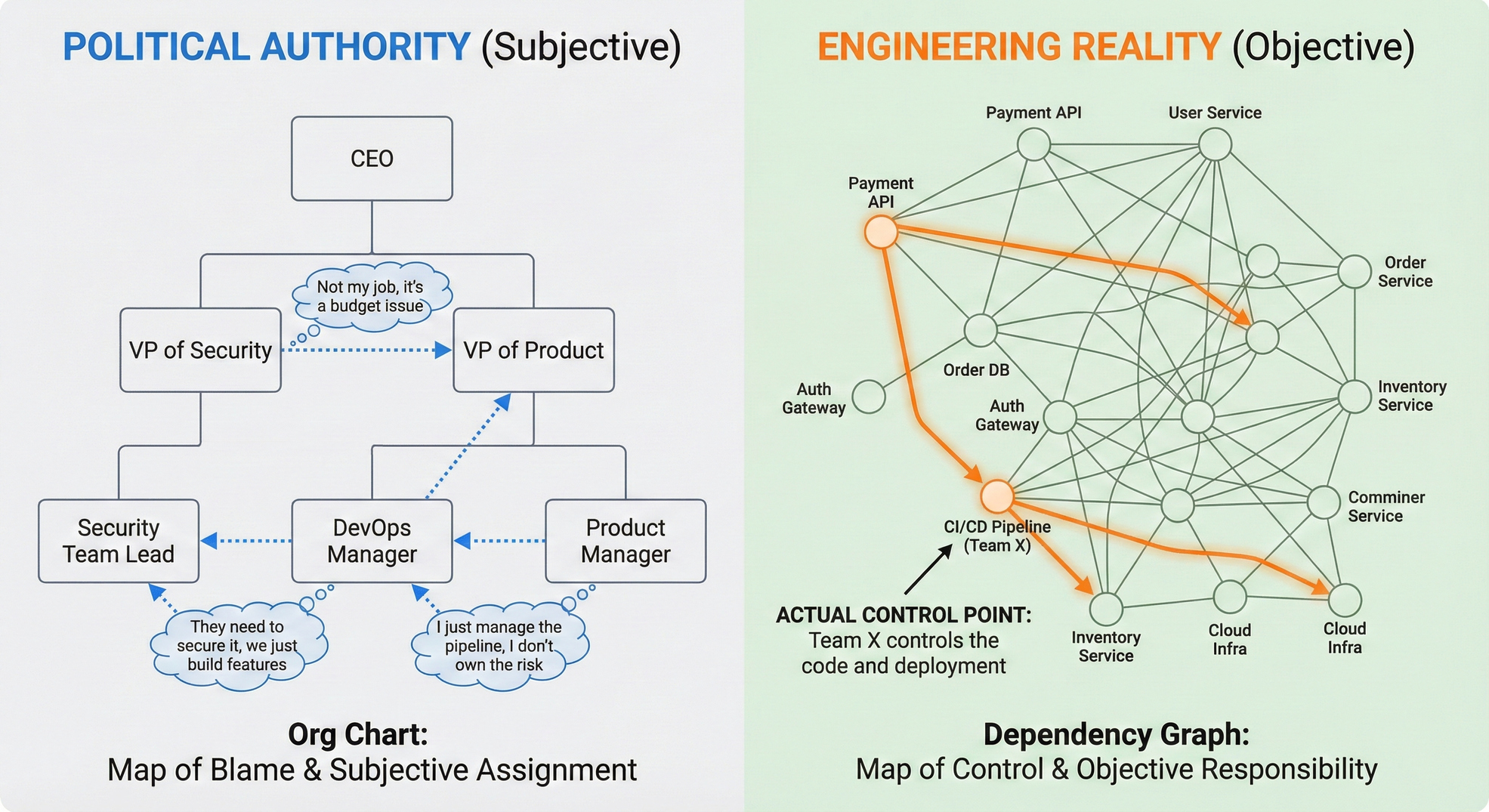

Turning Political Battles into Engineering Facts

Most responsibility conversations fail because they are subjective negotiations.

- Security says: "You should own this risk because it’s your app."

- DevOps says: "No, you should own it because it’s a firewall issue."

- Result: Standoff. Political battle—the loudest voice wins, not the logical one.

To fix this, we must move from Subjective Assignment (based on job titles) to Objective Assignment (based on system reality).

The Org Chart vs. The Dependency Graph

An organizational chart tells you who reports to whom. It is a map of political power. A dependency graph tells you which service calls which API. It is a map of actual control.

Example: The API Standoff Imagine an authentication gap in a microservice.

- The Political View: Teams argue over who "owns" security. Is it the Identity Team? The API Gateway Team? The Service Team?

- The Engineering Fact: Dependency mapping shows that Team X's CI/CD pipeline deploys the code, and Team X's repository contains the config file.

When you project the risk onto the dependency graph, the argument ends. You are not asking "Whose job should this be?" You are stating "Team X controls the lever that fixes this."

From "Not My Job" to "My Control Point"

This shifts the conversation from moral obligation ("You ought to fix this") to mechanical reality ("You are the only one able to fix this").

- You control the code → You control the Resources.

- You control the deployment → You control the Outcome.

- Therefore, you hold the Responsibility.

Data doesn't eliminate politics—nothing can—people will still argue about budget. But it removes the ability to hide. You can argue about funding the fix, but you can no longer argue about who must implement it.

From Abstract Theory to Calculated Consequence

The biggest enemy of responsibility is ambiguity. When a risk is presented as a "theoretical possibility" or just a "High Severity finding," it is easy for stakeholders to dismiss it.

- "It probably won't happen."

- "We have other priorities."

- "That sounds like a security problem, not a business problem."

To drive action, we must use technology to convert Abstract Risks into Calculated Business Outcomes.

The Role of Graph-Native Threat Modeling

This is where modern analytical tools change the game. By mapping the full graph of system dependencies—from code to cloud to business function—we can replace vague warnings with concrete evidence.

Instead of saying: "We have a vulnerability in the payment API." The analysis proves: "This vulnerability allows a lateral move to the Transaction Database. If exploited, it stops revenue collection ($50k/hour) and triggers a GDPR reportable event."

Connecting the Dots: Evidence Creates Accountability

When you present a risk this way, you change the psychology of the "Responsibility" conversation:

- It removes the "Theory" defense: You aren't guessing the impact; you are showing the blast radius on a graph. The risk is no longer a "maybe"—it is a calculated consequence waiting to happen.

- It defines the Business Outcome: It translates technical debt directly into Revenue and Resource terms. The stakeholder isn't accepting a "security ticket"; they are accepting a specific financial loss.

- It anchors Responsibility: When the evidence is this clear, claiming "not my job" becomes impossible. If you control the asset that causes the $50k/hour loss, you own the risk and—more importantly—the responsibility.

The tool becomes a mediator. A graph database doesn't care about your job title; it only cares about nodes and relations. It objectively:

- Identifies the Controller: "Team X's pipeline manages this asset." (The Who)

- Calculates the Consequence: "This asset controls the Revenue stream." (The Why)

and ending the argument instantly.

By linking the Engineering Fact (who controls it) to the Business Outcome (what happens if it breaks), you make the risk real. You strip away the ability to hide behind ambiguity.

The conversation shifts from "Who wants to own this ticket?" to "Who is willing to sign off on losing $50k/hour?"

The Bottom Line: Two Parallel Systems

We cannot ignore the reality of compliance. Auditors and frameworks (ISO, NIST, SOC2) require a "Risk Owner" column in your register.

So, here is the practical implementation: Run two parallel systems.

- For the Auditor (The Compliance Layer): Render unto Caesar—keep the "Risk Owner" title. Assign it based on the org chart. Let it satisfy the regulation. This is documentation.

- For the Business (The Operational Layer): Assign a "Responsible Party." Assign it based on the dependency graph—who actually controls the code, the budget, or the infrastructure. This is execution.

Do not confuse the two. The "Owner" signs the paper. The "Responsible Party" fixes the problem.

The Leadership Mandate

Ultimately, moving from one system to the other requires courage.

"Risk ownership" asks nothing of you but a signature. Responsibility asks for judgment. It requires you to optimize Revenue, Resources, and Risk simultaneously—a trade-off where the consequences are personal.

The leaders who thrive aren't the ones who minimize risk on paper. They are the ones who accept the burden of the trade-off in reality.

They are the ones who can look at the data, see the cost, and answer "Yes" when asked: "Can you take full responsibility for this decision?"

This article was originally published on Medium.