The Firewall Is Not Your Foundation

Why Secure Architecture Starts Without a Perimeter

Tell a traditional network architect to "add the firewall last" and they'll look at you like you suggested building a house without a foundation. To them, the firewall is the architecture.

That's the problem.

When the firewall is your foundation, everything inside it becomes one giant node of implicit trust. You're drawing a perimeter and hoping nobody gets past it, but that is not a secure, defendable architecture.

The Fully Connected Mesh You Didn't Design

When you design "firewall first," your mental topology looks like this:

Dangerous Things → [Firewall] → Cosy Inside

That "Cosy Inside" is doing a lot of heavy lifting. In graph terms, you've created a single supernode where every internal system can reach every other internal system. The firewall collapses thousands of relationships into one policy: outside bad, inside trusted.

The math is brutal. Before breach: Reachability(attacker) = 0%. After breach: Reachability(attacker) → 100%.

"Hold on, nobody runs a completely flat network anymore."

Segmentation reduces blast radius, that's real value. But it doesn't change the trust model. You haven't solved the problem; you've just broken your one giant implicit trust zone into fifty medium-sized implicit trust zones.

Inside the "App Segment," the database still trusts the web server implicitly. You haven't fixed the graph; you've just built smaller buckets. Post-breach reachability drops from 100% to maybe 20%. Better, but still a topology where one compromised node means the whole segment falls.

The Design-Time Gap: An Economic Trap

What does the "firewall first" actually mean for your architecture? You are making an operational promise that you cannot keep, and taking on a financial liability you cannot afford.

Start with the operational risk. You are assuming the firewall configuration (especially for internal segmentation) will be correct at deployment, correct after every change, and correct forever. But internal traffic is dynamic. Applications scale, IPs change, and dependencies shift. To keep up, you are forced to constantly churn rules. If you believe that rules are actually tightened and deleted as needed, you are betting your entire security posture on administrative perfection. In reality, rules accumulate, become overly permissive ("ANY/ANY"), and rot.

Now look at the economics. From a 3R Framework perspective (Revenue, Resources, Risk), internal firewalls are often a bad trade. You are burning expensive engineering hours and costly hardware to manage tens of thousands of brittle rules. And because the rules inevitably drift from reality, they provide a false sense of security.

The "Firewall First" model demands infinite resources to maintain a control that decays in value every day. By designing "Firewall Last," you stop throwing money at the impossible task of micro-managing a dynamic network with static lists.

What "Firewall Last" Forces You to Do

When you design as if the firewall doesn't exist, tough questions become unavoidable.

What is the minimum edge set required for this business to function? This is the question we identified in Zero Trust is Just Graph Theory with a Marketing Budget. You can't answer it by staring at a perimeter. You have to map actual dependencies: which services talk to which services, which users need which resources.

Can this node defend itself? If your database server requires a firewall to not get immediately compromised, that's not security architecture, that's life support. Designing without the firewall forces you to harden the actual components: authentication on every service, authorization on every request, encryption on every channel.

Architecture vs. Archaeology

You need to distinguish between architecture (design phase) and triage (operations phase).

"Firewall Last" is a design-time principle. It's the rule for everything you build next. When you are sketching a new microservices cluster or deploying a new cloud environment, assume the firewall does not exist.

Applying this retrospectively to a legacy mainframe is not architecture; it's archaeology. For those systems, the firewall is a constraint, not a choice. But for everything new, dependency on a firewall is a failed design review.

Why We Still Need Firewalls

Let's be clear: this is not an argument to delete your firewalls.

Firewalls remain a necessary line of defense. But in a "Firewall Last" architecture, their role shifts from structural dependency to strategic depth.

Once you have designed a secure graph where every node can defend itself, you add the firewall back in—consciously and with 3R awareness—to solve specific problems that identity cannot solve.

Even a perfectly secure web server shouldn't have to process 10 million packets per second from a botnet. A firewall drops this garbage in hardware, protecting your compute resources. When a new vulnerability like Log4j hits, you can't patch 5,000 servers overnight. The firewall (or WAF) buys you time. It adds another layer that attackers must bypass, even after compromising a node. Defense in depth only works when layers are independent—not when every layer assumes the perimeter holds.

Sometimes a regulatory body simply demands a network boundary. PCI-DSS, HIPAA, and others have explicit segmentation requirements. And systems that cannot defend themselves (mainframes, old ERPs, OT/SCADA) need to be isolated until they can be replaced.

The difference is dependency.

Firewall First: "If the firewall fails, we are breached."

Firewall Last: "If the firewall fails, we are busier, but we are not breached."

The ZTINO Problem

Surveys claim roughly half of organizations are "adopting Zero Trust." The reality is what security practitioners call ZTINO: Zero Trust In Name Only.

The pattern is predictable. Buy a "Zero Trust" product (identity proxy, ZTNA gateway). Layer it on top of the existing perimeter architecture. Keep all the implicit internal trust because refactoring is expensive. Declare victory.

Result: a firewall that's still a structural dependency, plus an identity layer that adds complexity without replacing the perimeter. Neither zero trust nor simplified operations, just a hybrid mess that requires maintaining both paradigms.

True zero trust isn't a product you bolt onto existing architecture. It's a topology that requires designing differently from the start.

The Legacy Anchor

This is the point where someone objects: "That's great for greenfield. What about my mainframe from 1997?"

Fair. Many critical systems—mainframes, legacy ERPs, OT/SCADA—were designed when "network security" meant physical cable access. They require flat networks and open protocols. They have no self-defense capabilities.

For these systems, the firewall isn't a design choice. It's a ventilator.

But this is technical debt, not architecture. The firewall isn't securing these legacy systems, it's keeping them on life support while organizations avoid the modernization conversation.

The honest path forward: design new systems firewall-last, and contain legacy systems behind the most restrictive boundaries possible until they can be replaced. Don't let the constraints of 1997 dictate the architecture of 2026.

The Firewall-Last Protocol

This is not a linear checklist; steps 1-3 are an iterative, joint design effort involving application, data, and infrastructure architects. You loop through these phases until the system topology itself is secure.

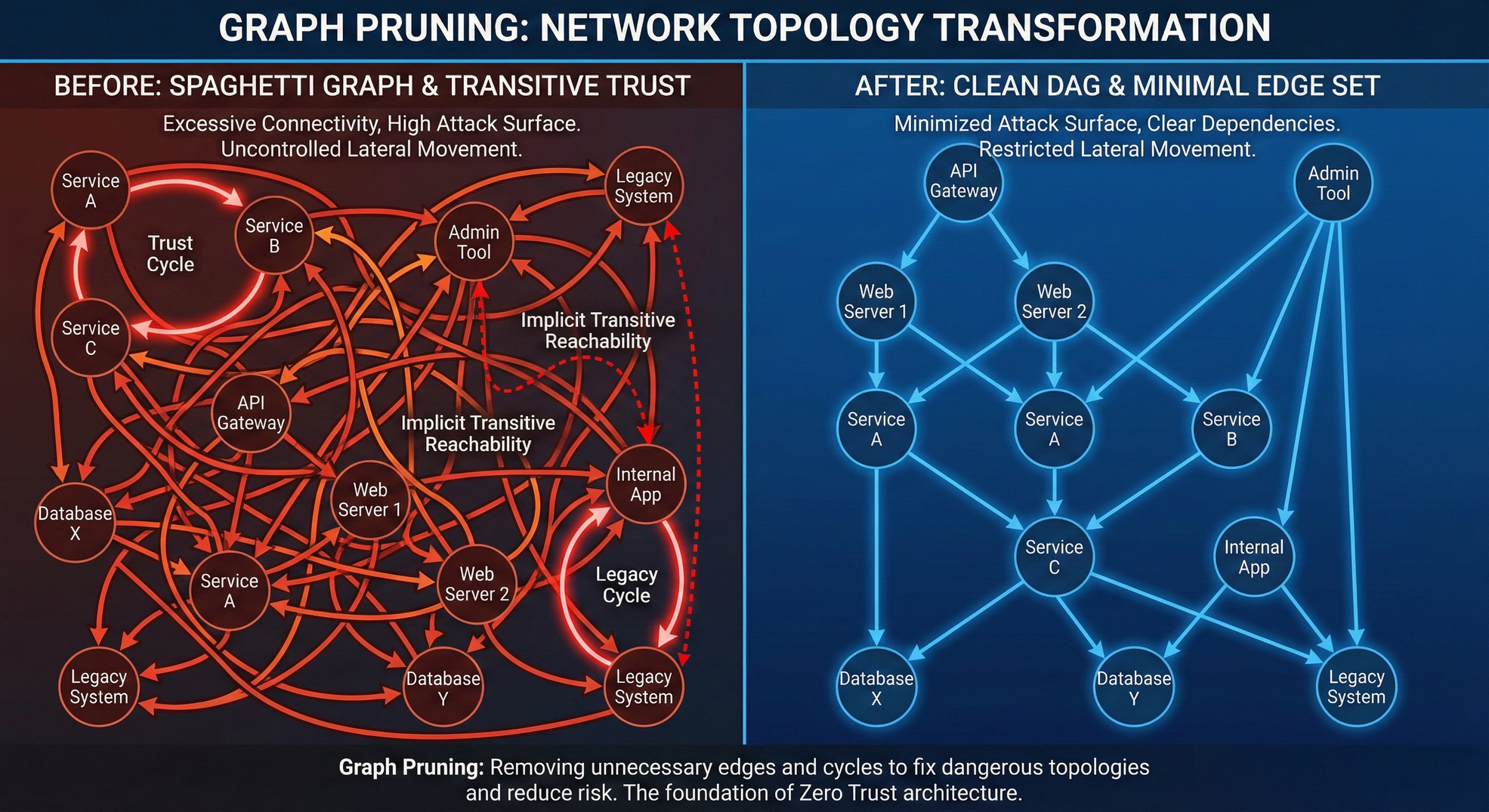

- Design and Prune the Graph

Map all nodes and the edges between them. Then apply graph theory to fix the dangerous shapes in your topology before you build it.- Minimize the edge set: Remove any connection not strictly required for business function. Every edge is a potential lateral movement path.

- Break the cycles: Look for trust loops (A trusts B, B trusts C, C trusts A). These enable indefinite lateral movement. Restructure dependencies to eliminate them.

- Identify chokepoints: Find the nodes that bridge different clusters: your "cut vertices." Control these and you control blast radius.

- Map transitive reachability: Just because A doesn't talk to C directly doesn't mean A → B → C isn't a valid attack path. Trace what's actually reachable, not just what's intentionally connected.

- Harden the Nodes

Every node must be able to defend itself. Authentication on every service. Authorization on every request. Encryption on every channel.

The test: Could this node survive on the public internet? If the answer is "no, it needs a firewall," you haven't finished hardening. You've identified a dependency. - Calculate Resource Constraints

Identity-based security handles authorization. It doesn't handle volume.

Identify where nodes might be overwhelmed: internet-facing services, high-traffic internal APIs, anything that can't shed load gracefully. These are candidates for network-level protection, not because they're insecure, but because they're finite. - Apply Firewalls

Now—and only now—add firewalls. This is not the foundation; this is for Residual Risk and Defense in Depth.- Noise filtering: Drop volumetric garbage before it hits application logic

- Virtual patching: Buy time when zero-days hit faster than you can patch

- Defense in depth: Add a layer that attackers must bypass even after compromising a node

- Compliance boundaries: Satisfy regulatory requirements that demand network segmentation

- Legacy containment: Isolate systems that can't defend themselves

The firewall is no longer a structural dependency. It's an optimization layer on top of an architecture that already works without it.

The Graph Makes It Concrete

The firewall-first architect draws a perimeter and fills in the details later. The firewall-last architect maps the connectivity, secures the nodes, and then places the firewalls exactly where they provide maximum value.

One of these approaches produces a fragile shell. The other produces a resilient architecture.

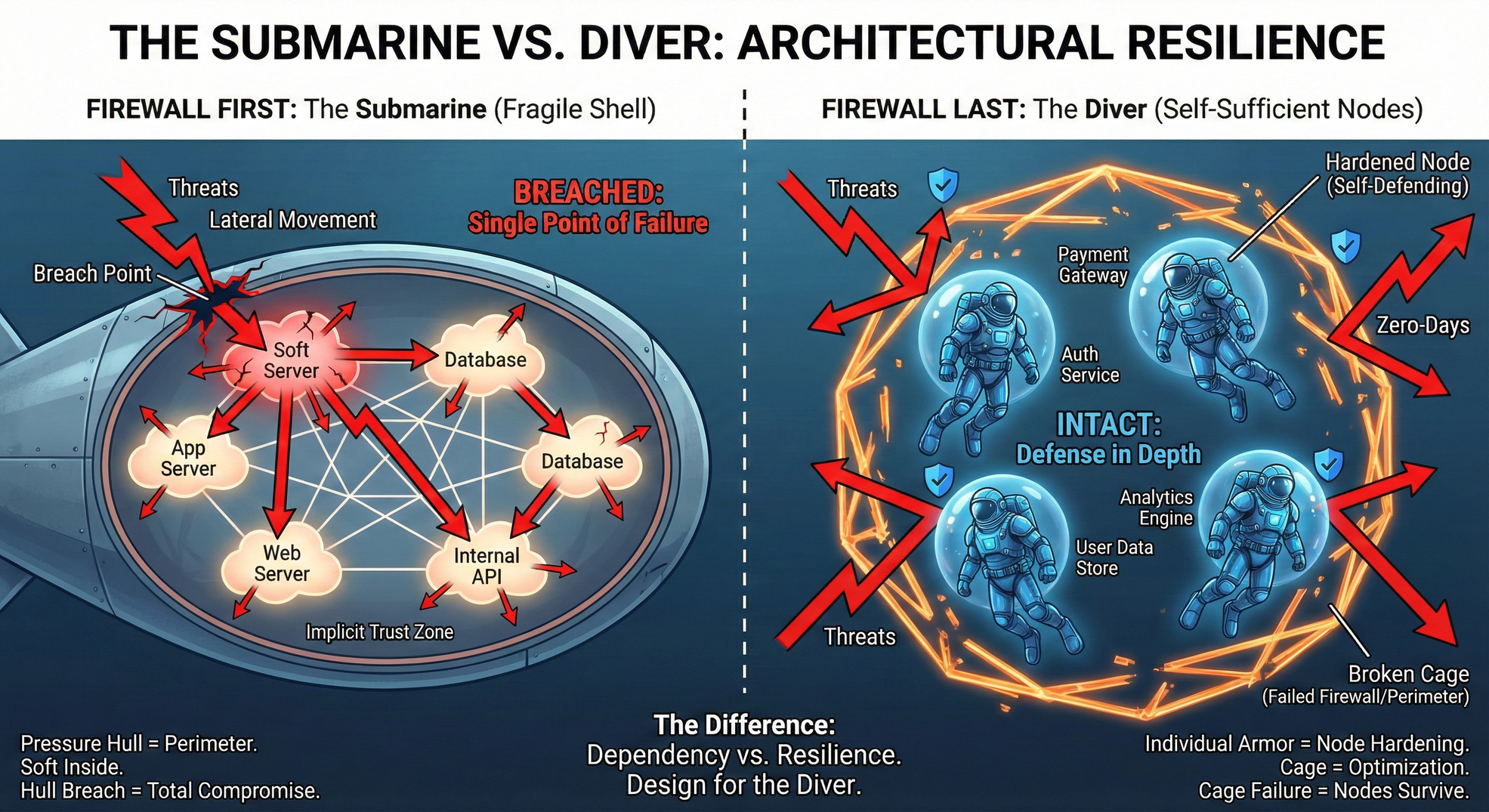

Think of it as the difference between a submarine and a diver.

Firewall First is a submarine. The network provides the pressure hull. Inside, the applications wear t-shirts. They are comfortable and unencumbered. But if the hull breaches anywhere, everyone drowns. The safety is entirely provided by the shell.

Firewall Last is a team of scuba divers. Every application wears its own suit and carries its own air. They are designed to swim in the open ocean. You might still put them in a shark cage (firewall) for extra safety, but if the cage breaks, they don't die. They are self-sufficient.

In the design phase, you must build divers, not submarines.

The test for your architecture: If every firewall failed simultaneously, would you be breached, or would you be busy?

If the answer is "breached," you have a firewall-first architecture wearing a zero-trust costume. If the answer is "busy but intact," you've built something resilient.

This approach shifts the firewall from "single point of failure" to "defense in depth." It's not about removing defense; it's about removing dependency.

--

This article originally published on Medium.