Beyond the Kill Chain: Modeling Attacks as State Machines

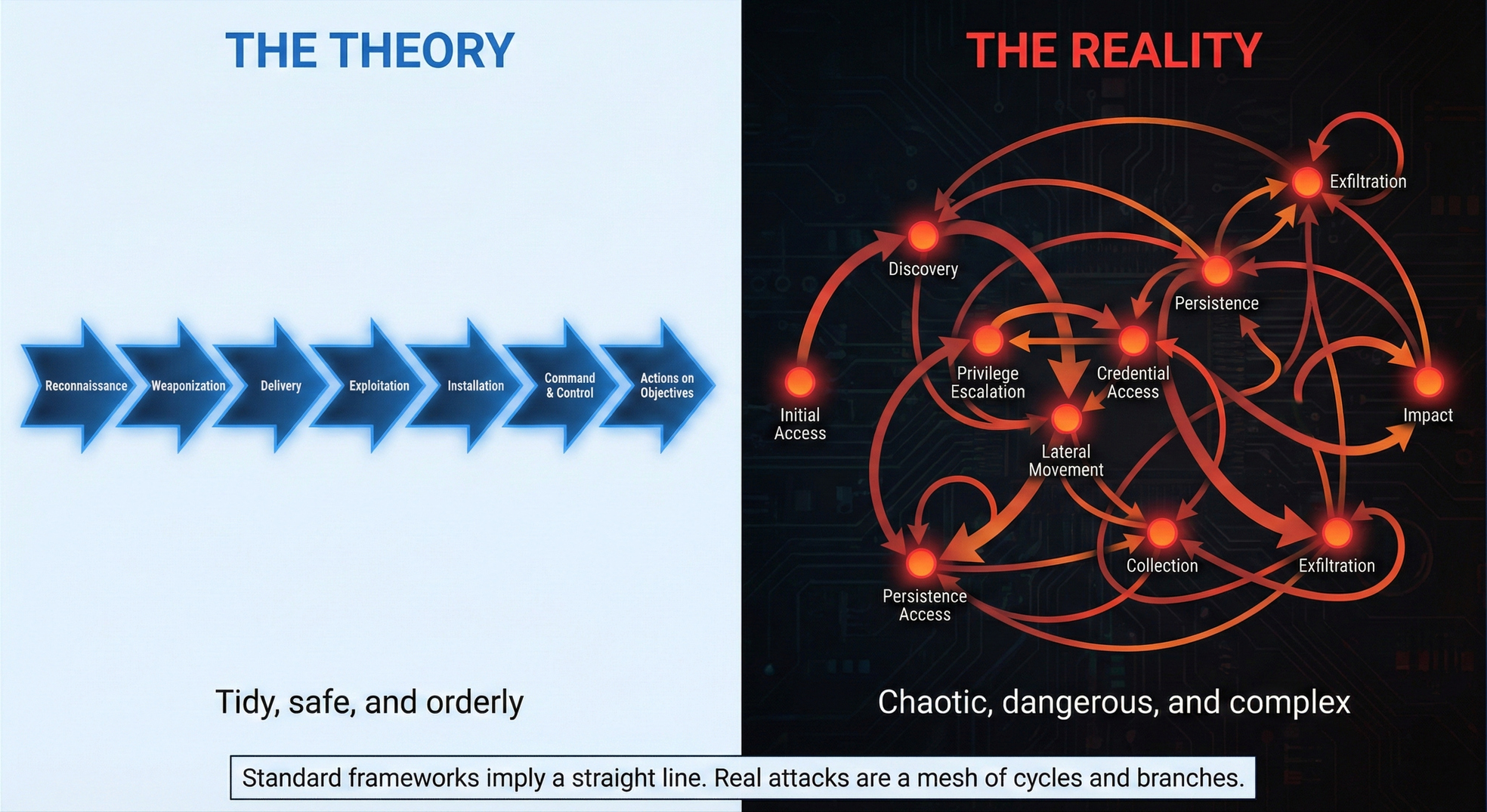

Security frameworks like the Lockheed Martin Kill Chain and MITRE ATT&CK have transformed how organizations understand threats. The Kill Chain provides a clear progression through attack stages. MITRE ATT&CK catalogs hundreds of attacker techniques with granular detail, platform-specific behaviors, and real-world examples. These frameworks are invaluable for threat intelligence, detection engineering, and red team planning.

But both frameworks share a critical gap: they model relationships as linear progressions.

The Kill Chain explicitly shows sequential stages with arrows between them. MITRE ATT&CK lists tactics in what appears to be temporal order: Initial Access → Execution → Persistence → and so on. Both suggest that attacks progress through stages sequentially.

This creates a mental model where attacks are linear progressions through phases—one stage leads to the next, and disrupting early stages stops the attack.

There's just one problem: real attacks don't work this way.

The Problem with Sequential Thinking

Here's what actually happens in real attacks:

An attacker gains initial access to a system. They execute code to establish persistence. They discover the network layout. They escalate privileges. They harvest credentials. They move laterally to another system.

And then? They start over. Discovery on the new system. Privilege escalation on the new system. More credential harvesting. More lateral movement.

This isn't a linear chain. It's a cycle:

Lateral Movement → Discovery → Privilege Escalation → Credential Access → Lateral Movement → ...

The kill chain metaphor breaks down because it can't represent this fundamental reality: attacks loop, branch, and adapt based on what they find.

Three Ways Graph Theory Reveals Attack Reality

When you model attacks as graphs (or more precisely, as state machines), the structure is straightforward:

- States are attack tactics (MITRE ATT&CK tactics like Initial Access, Execution, Discovery, Lateral Movement)

- Transitions are the edges between states (e.g., "Discovery → Lateral Movement" or "Credential Access → Privilege Escalation")

Think of each attack as moving through different states. Unlike linear chains where you progress through each state once in sequence, state machines allow:

- Returning to previous states (loops)

- Multiple paths from the same state (branches)

- Context-dependent transitions (which path you take depends on what you find)

This reveals three critical patterns that linear models miss entirely.

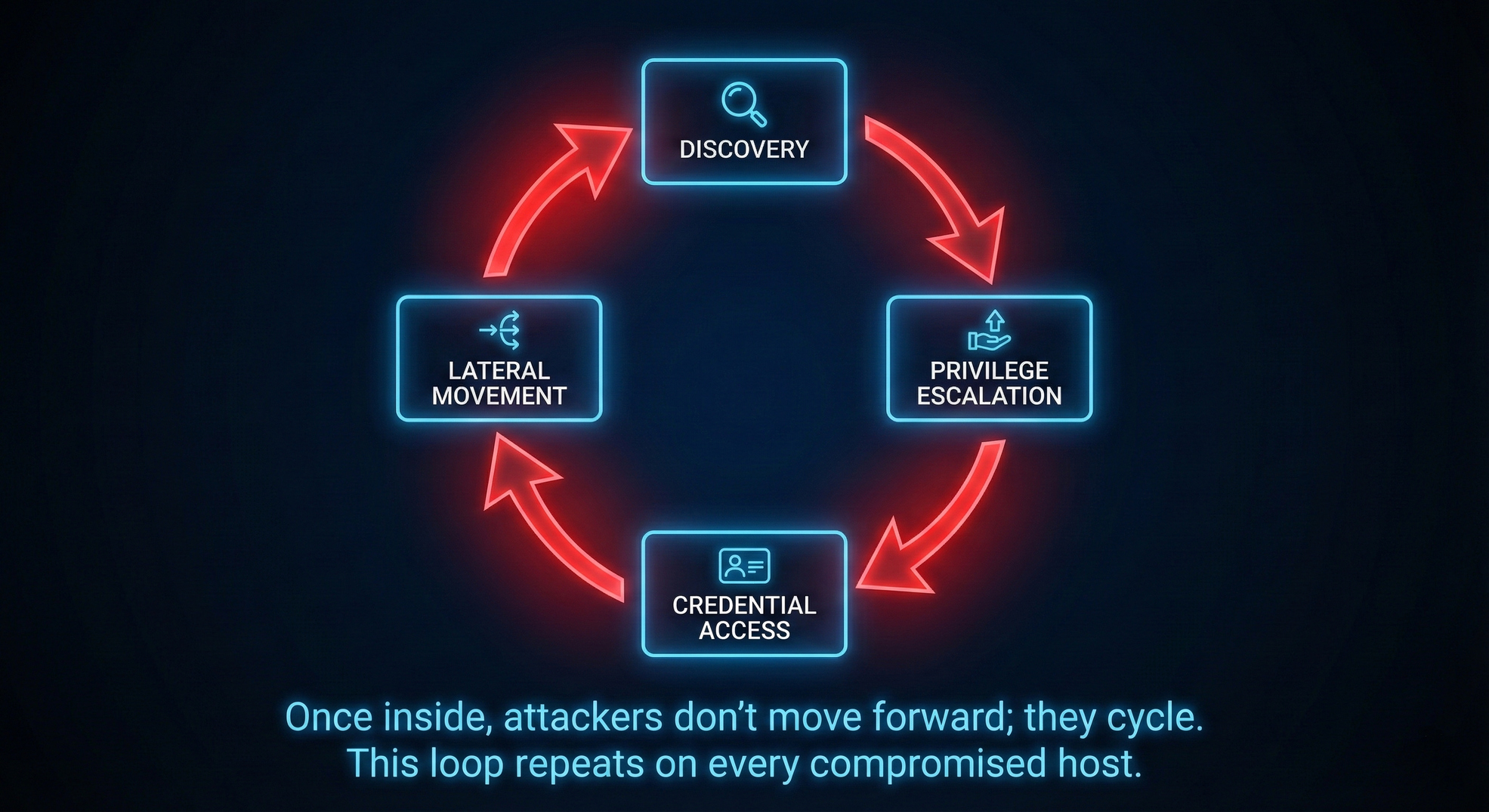

1. Attacks Have Cycles

The lateral movement loop is the most obvious example.

After an attacker moves laterally to a new system, they don't continue in some predefined sequence. They restart critical tactics:

- Discovery (again): What's on this new system? What can it reach? What data is here?

- Privilege Escalation (again): Can I get higher privileges on this system?

- Credential Access (again): What credentials are cached or stored here?

- Lateral Movement (again): Where can I go from here?

This creates a feedback loop. Each successful lateral movement opens new discovery opportunities. Each discovery identifies new lateral movement targets. The cycle continues until the attacker either achieves their objective or gets disrupted.

Strategic implication: Disrupting the lateral movement cycle is often more effective than blocking initial access. Once inside, attackers will cycle through lateral movement dozens of times. Breaking this cycle stops the attack progression regardless of how they got in initially.

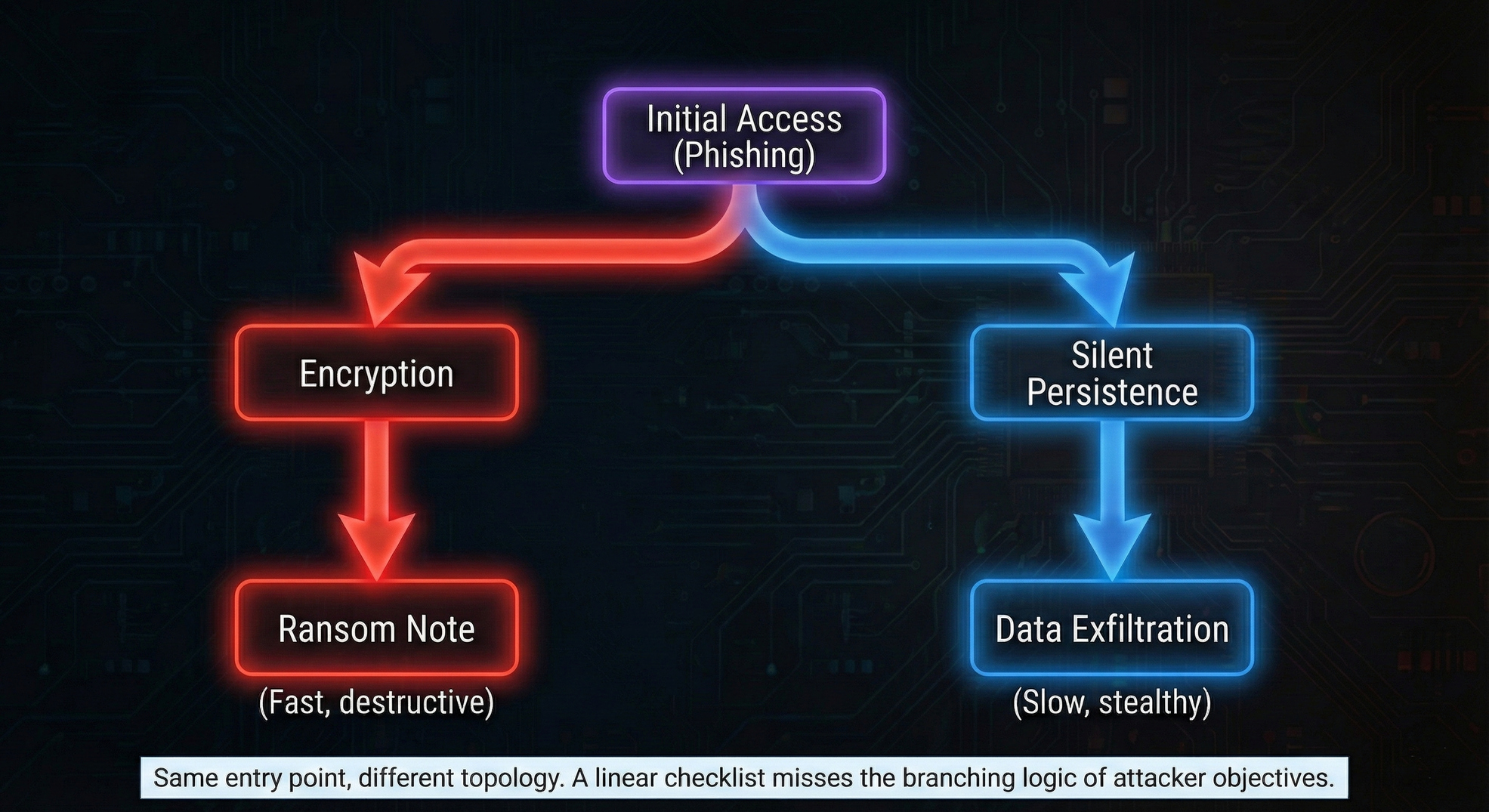

2. Attacks Have Branches, Not Sequences

The kill chain suggests a single path forward at each stage. Reality is messier.

After gaining code execution, attackers face multiple parallel objectives:

- Establish persistence (maintain access if they lose it)

- Escalate privileges (get higher permissions)

- Discover the environment (understand what's available)

- Establish command & control (communicate with attacker infrastructure)

These aren't sequential steps—they're branching paths that can be pursued in parallel or in different orders depending on what the attacker finds.

Example: Two different paths from the same starting point

Path A (data theft):

Execution → Discovery → Credential Access → Lateral Movement → Collection → Exfiltration

Path B (ransomware):

Execution → Privilege Escalation → Credential Access → Lateral Movement → Persistence → Impact

Same entry point, different objectives, different tactical sequences. A linear model can't represent this branching reality.

Strategic implication: Defenders can't just "block early stages" because different attack objectives take different paths. You need to understand which paths matter most for your environment and your critical assets.

3. Context Changes Everything

The same attack tactic has radically different importance depending on your environment.

Cloud environments:

In AWS or Azure, privilege escalation often means exploiting overly permissive IAM roles. Lateral movement might mean switching between accounts or exploiting cross-service permissions. Initial access might not even involve traditional network entry—misconfigured S3 buckets or exposed APIs provide direct access to data.

The attack graph structure for cloud environments emphasizes different transitions than on-premises networks.

Industrial control systems (ICS/OT):

Attacks on industrial systems have fundamentally different graph structures. There's often an air gap between IT and OT networks, creating a bifurcated graph where attackers must bridge between two separate network architectures. Impact isn't just data theft—it's physical damage or safety system compromise.

Small/medium businesses:

SMB environments often have compressed attack graphs with fewer hops between initial access and critical assets. Lateral movement paths are shorter due to simpler network architectures. But credential reuse is more common, making privilege escalation easier.

Strategic implication: Generic security guidance ("focus on prevention") doesn't account for environmental context. A graph-based approach lets you model your specific environment and optimize defenses for your actual attack surface.

What This Means for Your Security Strategy

If attacks are graphs, not chains, your defensive strategy needs to change.

Stop Prioritizing "Early Stage" Defenses

The kill chain creates a bias toward "left of boom" thinking: stop attacks before they start. This leads to overinvestment in perimeter defense and underinvestment in internal detection and response.

But once attackers are inside (and they will get inside), the "early stages" are irrelevant. The lateral movement cycle becomes the dominant pattern. If you've invested everything in preventing initial access and nothing in detecting lateral movement, you've optimized for the wrong problem.

Better approach: Identify which transitions are critical in your environment. These vary based on your architecture, data sensitivity, and threat model.

Examples of transitions that are often (but not always) critical:

- Discovery → Lateral Movement (if you can blind attackers, they can't find targets)

- Credential Access → Lateral Movement (valid credentials enable movement across networks)

- Lateral Movement → Collection (limits blast radius by detecting movement toward data)

The point isn't to follow a universal checklist. The point is to analyze your specific environment's attack graph and find where disruption has maximum impact.

Understand Your Critical Paths

Not all attack transitions are equally important. Some paths are critical dependencies—the attack cannot succeed without them. Others are enhancement relationships—they make the attack easier but aren't strictly required.

Example: Credential access enables lateral movement

In most enterprise environments, lateral movement relies heavily on valid credentials. Attackers use harvested credentials to authenticate to remote systems legitimately, bypassing network-level detection.

This makes the transition Credential Access → Lateral Movement a critical path in many enterprise networks. If you can prevent credential harvesting or detect credential abuse, you significantly disrupt the most common lateral movement method—though attackers could still move laterally through vulnerability exploitation or other means.

Compare this to Reconnaissance → Initial Access, which is often treated as critical in kill chain thinking. But attackers don't need reconnaissance to gain initial access—phishing, credential stuffing, and vulnerability exploitation work without reconnaissance. Blocking reconnaissance doesn't stop the attack.

Better approach: Map which transitions are critical dependencies in your environment. Focus defensive investments on disrupting these critical paths rather than following generic "best practices."

Account for Attack Cycles

Linear models assume attacks progress through stages once. Graph models reveal that attackers cycle through certain tactics repeatedly.

The lateral movement cycle is the most important:

Lateral Movement → Discovery → Privilege Escalation → Credential Access → (back to Lateral Movement)

Each iteration of this cycle expands the attacker's reach. They discover new systems, harvest new credentials, escalate privileges on new machines, and move laterally again.

Strategic implication: Defensive strategies that disrupt this cycle are multipliers. If you can detect or block any part of the cycle, you force attackers to restart or try alternative (often noisier) methods.

Network segmentation, for example, doesn't prevent initial access or discovery—but it disrupts the lateral movement cycle by limiting where compromised credentials can be used. This forces attackers into more detectable behavior.

From Theory to Practice

This isn't just academic musing. Graph-based attack modeling enables concrete improvements:

Resource allocation: Instead of distributing security budget across generic categories ("network security," "endpoint protection," "awareness training"), you can calculate which defensive investments disrupt the highest-value attack paths in your environment.

Threat modeling: When evaluating architectural changes, you can model how the change affects attack graph structure. "If we connect service A to service B, what new attack paths does that create?" becomes answerable with graph analysis.

Red team planning: Penetration testers can identify highest-probability attack paths rather than following generic playbooks. This creates more realistic attack simulations.

Vendor evaluation: Security products can be evaluated based on which attack transitions they disrupt, not just generic feature lists. "Does this tool prevent credential harvesting?" is more valuable than "Does this tool have AI?"

The Broader Insight

The shift from kill chains to graphs isn't just about attack modeling. It's about recognizing that security is fundamentally about relationships.

- Which systems connect to which systems

- Which users can access which resources

- How data flows through your infrastructure

- What attack paths exist between entry points and critical assets

- Where security controls create protection

These are all relationship questions. Linear models can't capture relationships. Graphs can.

Organizations that recognize this shift their security thinking from "what are my assets?" to "how are my assets related?" That shift unlocks capabilities that linear frameworks simply can't provide.

The Bottom Line

The Kill Chain and MITRE ATT&CK are valuable frameworks—they provide structure, vocabulary, and shared understanding for security teams. Organizations need these frameworks to communicate about threats, map defenses to attack stages, and guide security investments.

But these frameworks weren't designed to model attack dynamics. Real attacks cycle through lateral movement loops. They branch based on what they discover. They adapt to environmental context. They restart tactics on each new system.

Graph theory provides a framework for modeling these dynamics. And when your model reflects reality, your defensive strategies improve.

The question isn't whether attacks are graphs. They always have been. The question is whether your security strategy acknowledges this reality.

The path forward: Use MITRE ATT&CK as the vocabulary (tactics and techniques), but layer graph relationships on top to model how tactics connect, which transitions matter most, and where defensive investments create maximum disruption.

This is why we built dethernety on top of MITRE ATT&CK, adding graph-based relationship modeling to show attack paths through your actual system architecture. When your core problem is relationships and paths, your tooling should be built for relationships and paths. Learn more about graph-based threat modeling.

This article was originally published on Medium