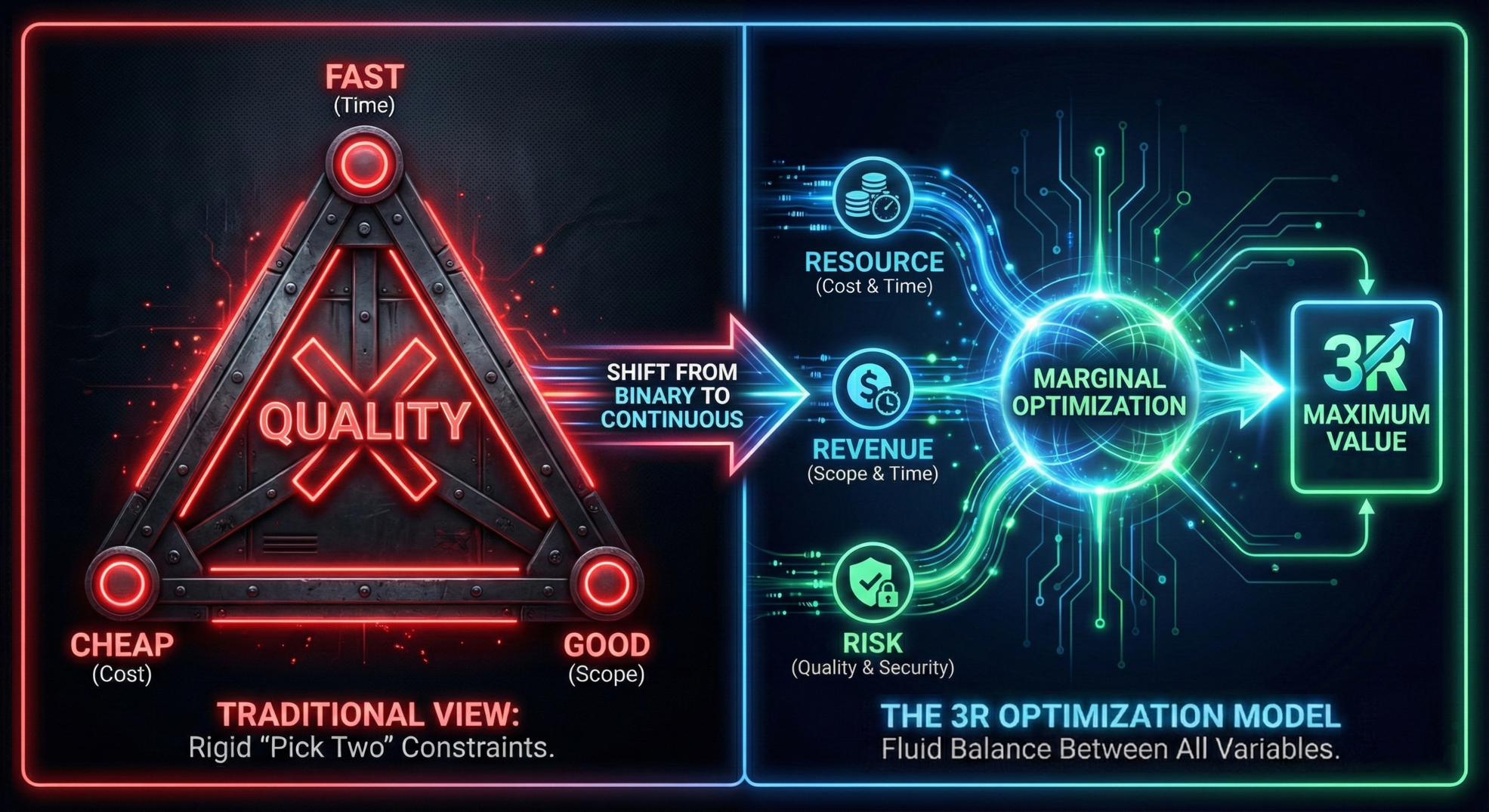

From Binary Trade-offs to 3R Optimization

Every project manager has heard it: "Fast, cheap, good - pick two."

Every security team hears the same thing: "Secure, usable, affordable - pick two."

Both are wrong for the same reason.

The Iron Triangle Explained

The classic Project Management Triangle defines three primary constraints: Time, Cost, and Scope, with Quality sitting in the center as the outcome.

The conventional wisdom — “Pick Two” — dictates that you can only optimize two dimensions at the expense of the third.

- Want it fast and cheap? Quality suffers.

- Want it fast and good? It will be expensive.

- Want it cheap and good? It will take forever.

This model persists not because it is mathematically precise, but because it is psychologically convenient. It simplifies a complex optimization problem into a binary choice.

Most dangerously, it provides a ready-made excuse for failure. It absolves teams from making difficult decisions by allowing them to shrug and say, “Well, the math says we had to sacrifice quality because we chose speed and budget.”

But in the real world, you don’t “pick two.” You deliver “fast enough, cheap enough, good enough.” You are always balancing all three. The Iron Triangle obscures this reality by forcing you to choose corners rather than adjust levers.

The Correct Approach: Optimization

The right question isn't "which two dimensions should I prioritize?" The right question is: "where does spending one more dollar (or one more hour) yield diminishing returns?"

This is marginal analysis. Different projects have different optimal points:

- NASA mission: quality matters far more than cost or time

- Startup MVP: time matters far more than quality or cost

- Enterprise software: balance depends on the specific context

There's no universal "pick two" rule because the optimal point varies by situation - but in every case, you're balancing all three to maximize overall value.

NASA prioritizes quality not because they "picked quality and cost" - but because low quality creates catastrophic risk that destroys overall value. Startups prioritize time not because they "picked time and resources" - but because delayed launch destroys revenue that outweighs quality risks.

In both cases, all three factors affect the decision. The question is always: "What combination of time/scope, cost, and quality creates maximum overall value?" Not "which two do I pick?"

The Upgrade: Mapping Constraints to Value

The Iron Triangle fails because its variables are categorized by input (Time, Scope, Cost) rather than business outcome.

To make better decisions, we must translate these inputs into the 3R Optimization Model.

- Scope → Revenue: In the old model, “Scope” is just a list of features. In the 3R model, Scope represents Revenue.

- More features = higher potential value to the customer.

- Cutting scope isn’t just “doing less work”; it is explicitly reducing the Revenue potential of the release.

- Cost → Resources: This is the only direct mapping. “Cost” becomes Resources — the budget, people, and infrastructure consumed to deliver the project.

- Quality → Risk: The Iron Triangle treats “Quality” as an abstract outcome. The 3R model treats lack of quality as Risk.

- Defects, technical debt, and security vulnerabilities are not just “poor quality” — they are quantified financial exposures.

- Low quality increases the probability of future resource drain (incident response) or revenue loss (reputation damage).

- Time → The Multiplier (The Critical Flaw): This is where the Iron Triangle is mathematically misleading. It treats Time as a single constraint, but Time actually acts on two dimensions simultaneously:

- Time → Revenue (Opportunity Cost): Shipping earlier captures revenue sooner and secures first-mover advantage. Delay destroys revenue.

- Time → Resources (Burn Rate): Every day of development costs money. Extending timelines compounds overhead; rushing timelines triggers premium overtime costs.

By splitting “Time” into its actual financial components — Revenue Opportunity vs. Resource Burn — we stop asking “Can we meet the deadline?” and start asking the optimization question:

“Does the Revenue gained from launching 2 months early justify the premium Resource cost and the increased Risk exposure?”

Real-World Example: The 24-Month Horizon

Let’s look at a decision to release a new enterprise feature. Feature Value: Generates €50k/month in revenue. Lifecycle: We expect this software to run for 2 years (24 months). The Decision:

- Option A (Rush): Launch now (Month 1). Cheaper build (€80k), but creates “spaghetti code” and security exposure.

- Option B (Quality): Launch in 2 months (Month 3). Higher build (€120k), but clean architecture and secure by design.

The “Iron Triangle” View: Option A is Faster (2 months earlier) and Cheaper (€40k less upfront). Under the “Pick Two” logic, Option A wins easily.

The 3R Optimization View: When we calculate the Net Lifecycle Value (Revenue — Resources — Risk), the picture changes completely.

| Dimension | Option A: "Rush" (Fast & Cheap) | Option B: "Quality" (Balanced) |

|---|---|---|

| Revenue | €1,200,000 (24 months of sales) | €1,100,000 (We lose €100k waiting to launch) |

| Resources | €200,000 (€80k build + high maintenance) | €144,000 (€120k build + low maintenance) |

| Risk | €100,000 (20% chance of €500k breach) | ~ €0 (Secure by Design) |

| NET VALUE | €900,000 | €956,000 |

Application to Security: The “Shadow IT” Equation

Security teams face their own version of the Iron Triangle: “Secure, Usable, Affordable — pick two.”

This binary thinking is the root cause of friction between CISOs and the business.

- Pick Secure & Affordable (Ignore Usability): You implement a locked-down system. Users hate it, find workarounds, and move data to unauthorized cloud apps.

- Pick Usable & Affordable (Ignore Security): You ship fast, but the product is full of vulnerabilities.

- Pick Secure & Usable (Ignore Cost): You buy best-in-class tools, but blow the budget and get vetoed by the CFO.

Applying the 3R Model: Instead of picking two, use the 3R framework to calculate the hidden costs of “bad” choices.

- Usability → Revenue

In security, “Usability” is not a nice-to-have; it is a Revenue driver.- If a control is hard to use, employee productivity drops (Internal Revenue loss).

- If customer login is difficult, churn increases (External Revenue loss).

- Optimization Question: “Does the €50k saved by buying the ‘cheap’ MFA solution cost us €200k in lost employee productivity?”

- The Paradox of “Ignoring Usability”

The Iron Triangle suggests that if you sacrifice Usability, you simply get a “less usable” product. The 3R Model reveals the truth: Low Usability increases Risk. When security is “Secure and Affordable” but impossible to use, users create Shadow IT. They bypass your controls.- Result: You paid for the tool (Resources), killed productivity (Revenue), and still have the breach exposure (Risk) because users aren’t using the tool.

The Shift: Stop asking: “How can we make this secure within budget?” Start asking: “What is the optimal friction level where we maximize security adoption (Risk reduction) without destroying user productivity (Revenue)?”

The Executive Mandate: Change the Questions

The “Pick Two” mentality survives because it is safe. It gives teams a mathematically seemingly sound excuse to ignore difficult variables.

As a leader, you destroy this heuristic by changing the questions you ask in project reviews.

Stop asking: “We are over budget — what features can we cut?”

Start asking: “If we cut this scope, how much Revenue potential are we deleting? Is that loss greater than the cost of the delay?”

Stop asking: “Is this secure?” (A binary yes/no)

Start asking: “What is the residual Risk exposure in dollars if we launch now, and does the early Revenue justify accepting that Risk?”

Stop asking: “Can we have this faster?”

Start asking: “What is the premium Resource cost to expedite this, and does the first-mover advantage cover that premium?”

When you demand marginal analysis instead of binary trade-offs, you force your teams to do the math.

Common Objections Addressed

"But sometimes constraints are real!"

True. But even with real constraints, the optimal point is still a balance, not "pick two." If you have a hard deadline, you're optimizing resources and risk within a time constraint - still three dimensions.

"This sounds complicated!"

It's actually simpler than arbitrary "pick two" choices. You're just making the implicit trade-offs explicit and quantifying them instead of guessing.

"We don't have data to quantify everything!"

Estimates are better than no analysis. And uncertainty narrows with better tools - which is why investing in analytical capabilities (for risk assessment, resource planning, revenue forecasting) improves decision quality.

“Everyone knows ‘Pick Two’ is just a joke. No one follows it literally.”

We might not follow it strategically, but we follow it subconsciously in micro-decisions. When a developer decides to skip a security check to meet a sprint deadline, they are applying “Pick Two” logic at the execution level.

A perfect strategy can be completely ruined by thousands of micro-decisions made using the wrong heuristic.

If your high-level strategy is “Optimization,” but your ground-level culture is “Pick Two,” the culture will win. The 3R Optimization Model gives teams the tool to align those micro-decisions with the macro-strategy.

The Bottom Line: From Binary to Balanced

The Iron Triangle captures an important truth: you can't optimize everything simultaneously. But the "pick two" interpretation is mathematically wrong.

The correct interpretation: find the optimal balance across all dimensions using marginal analysis.

The 3R Optimization Model provides clearer language for this optimization:

- Revenue - explicitly captures both scope (what creates value) and time (when value is captured)

- Resources - captures cost plus time's burn aspect (what we spend, including the cost of time itself)

- Risk - makes quality explicit as quantified exposure (not just an outcome)

The key improvement: the 3R Optimization Model separates time's dual effects. Instead of "time" affecting both revenue and resources ambiguously, you calculate each effect separately. This enables precise trade-off analysis.

This precision enables better decisions. Organizations that move from "pick two" thinking to "optimize three" thinking consistently outperform those stuck in binary trade-offs.

The goal isn't to have it all. The goal is to find the right balance for your specific situation - and to make that choice consciously, with data, rather than unconsciously with heuristics.

Stop asking "which two can I optimize?" Start asking "what's the marginal return on the next dollar spent?" That's the shift from binary constraints to optimization.

This article was originally published on Medium