Alert Fatigue Is an Autoimmune Disease

Why modern SOCs suffer from "autoimmune disease," and how Immune Network Theory solves the signal-to-noise problem.

Security vendors love the immune system analogy. "Our EDR is like white blood cells." "Our SIEM detects threats like antibodies." It sounds scientific. It sounds sophisticated.

It's also wrong.

A burglar alarm detects an intruder and screams. That's what most SIEMs do. They match patterns and generate alerts. Detection without regulation.

A real immune system is different. It detects threats, yes, but it also regulates itself. It knows when to attack and when to stop. It maintains balance.

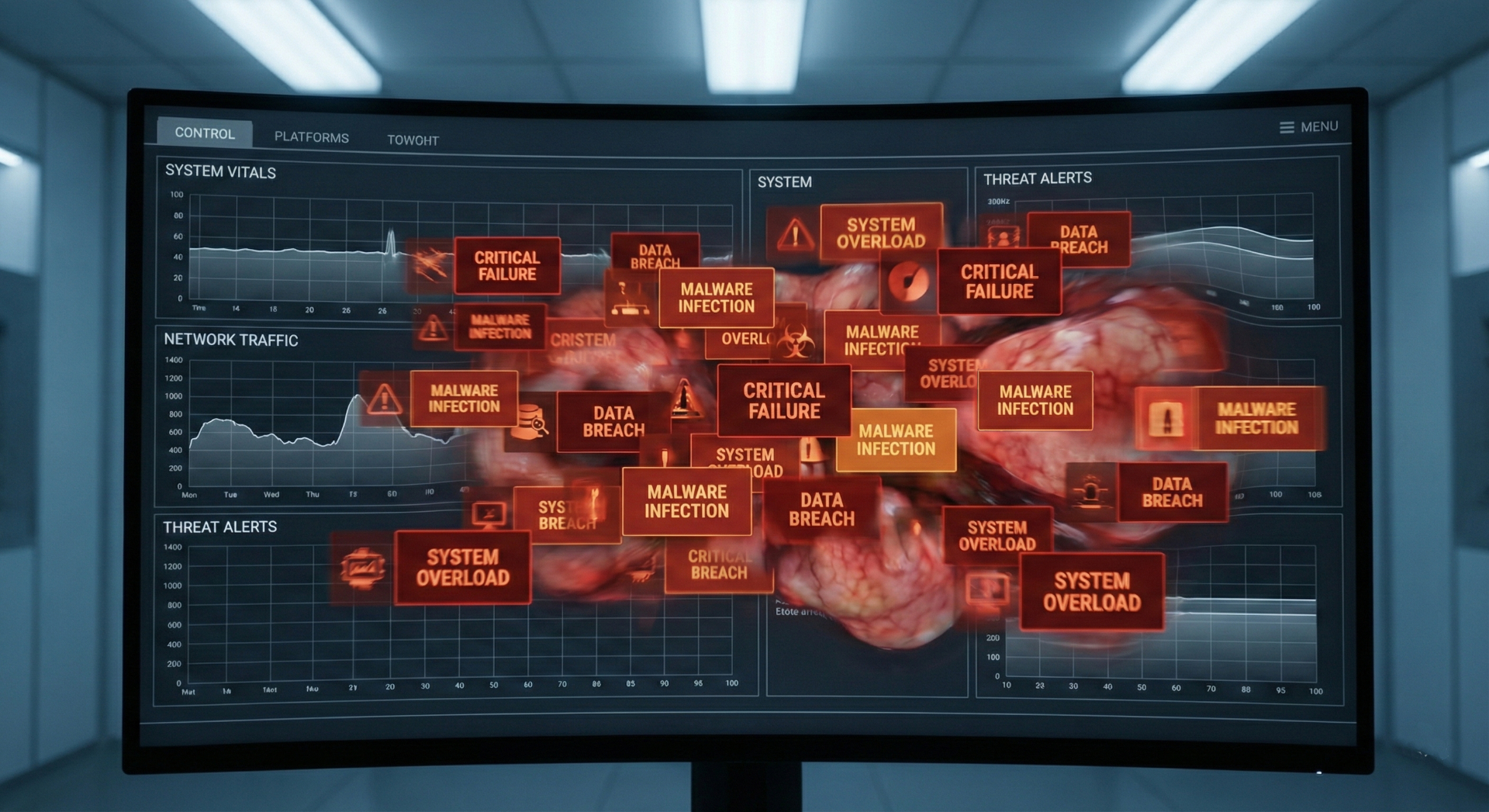

The difference isn't semantic. It's the difference between a SOC that functions and a SOC drowning in 10,000 alerts per day, chasing ghosts while real attackers walk through the noise.

The science most security people get wrong

When security professionals invoke the "immune system," they're usually thinking of Clonal Selection Theory, the 1950s model where the immune system works like a lock and key. Pathogen enters, matching antibody recognizes it, immune response destroys it. Simple. Linear. One threat, one response.

This maps neatly onto signature-based detection: malware enters, signature matches, alert fires. And Clonal Selection is still how individual immune responses work. But it only explains half the picture: how the immune system attacks. It says nothing about how the immune system stops attacking.

In 1974, Niels Jerne asked that second question. His answer, Immune Network Theory, argued that the immune system is a network, a graph where immune components communicate with each other as much as they communicate with threats.

Antibodies bind to other antibodies.

This creates feedback loops. Stimulation and suppression. Regulation. The immune system maintains homeostasis, internal balance, instead of just reacting to threats.

Jerne won the Nobel Prize for this work. His insight maps onto what's broken in modern security operations.

The SOC has autoimmune disease

What happens when an immune system loses its regulatory network? It attacks itself. Lupus. Crohn's disease. Allergies. The detection machinery works fine, too well in fact. Without suppression loops, the system can't distinguish "self" from "non-self," and it destroys healthy tissue while exhausting the body's resources.

This is exactly what's happening in your SOC.

Modern security operations have invested heavily in detection: EDR, NDR, SIEM, CASB, email security, cloud security posture management. Each tool is a high-gain detector, tuned to be sensitive to potential threats.

But detection without regulation creates a predictable failure mode:

- Vectra's 2024 State of Threat Detection survey of 2,000 SOC practitioners found the average team receives 4,484 alerts per day. 62% go entirely ignored.

- Alert fatigue. 71% of practitioners worry they'll miss a real attack buried in the noise.

- A 2023 Morning Consult/IBM survey found SOC professionals consider 63% of daily alerts false positives or low-priority. The SOC is attacking "self," flagging legitimate users and normal operations.

- That same IBM survey measured analysts spending roughly a third of their workday investigating alerts that turn out to be nothing.

- Burnout and turnover. A 2025 Sophos survey of 5,000 IT and cybersecurity professionals across 17 countries found 76% experiencing burnout. Vectra's 2024 data is worse: 67% are considering leaving or actively leaving their jobs. The human components of the system fail under load.

In immunological terms, your SOC is having a cytokine storm, an unregulated inflammatory response that causes more damage than the original threat. The body's defense system becomes the disease.

The symptoms are familiar:

- Legitimate traffic blocked because it "looked suspicious"

- Business-critical applications flagged as malware

- Real attacks missed because they were buried in noise

This isn't a detection problem. You have plenty of antibodies. It's a regulation problem. You're missing the network.

What Jerne knew that your SIEM doesn't

Jerne's Immune Network Theory introduced a concept called the idiotypic network. In simplified terms: antibodies have unique shapes (idiotypes), and other antibodies can recognize and bind to those shapes. This creates a web of mutual recognition, antibodies regulating antibodies.

The result is a system with three properties that most SIEMs lack:

- Self-tolerance. The immune system learns what "self" looks like and actively suppresses responses to it. Without this, you get autoimmune disease. In security terms: your SIEM should know what normal looks like and suppress alerts for baseline behavior.

- Response regulation. When an immune response begins, it doesn't continue forever. Suppressor mechanisms activate to prevent runaway inflammation. For a SOC, this means context should suppress or amplify alerts based on what else is happening in the environment.

- Network memory. The immune system remembers patterns of response, not only individual pathogens. It learns which reactions were appropriate and adjusts future behavior. Your detection system should learn from analyst decisions as much as from threat intelligence feeds.

A SIEM that matches signatures and fires alerts has none of these properties. It's a collection of independent detectors with no interconnection. Every alert exists in isolation. There's no network, just a list.

Building the idiotypic network in your SOC

Jerne described the immune system as a functional network. Nodes (immune components) connected by edges (regulatory relationships). Some edges stimulate. Some edges suppress. The network topology determines the system's behavior.

A graph-based security architecture works the same way.

Example: the new admin account

In a traditional SIEM:

- Alert: "New admin account created on Server X." Severity: High.

- An analyst checks the HR system, finds an onboarding event for a new hire, and closes the ticket.

A SIEM correlation rule can even automate this: if admin account creation + onboarding event within 24 hours, suppress. Two events, one rule. But neither the analyst nor the rule asked whether the onboarding event itself was legitimate.

In a graph-based architecture, suppression is a chain of verification across systems:

- Node A: New Admin Account Alert (Server X)

- Node B: HR Onboarding Event (new hire, IT department)

- Node C: Payroll record (matching employee, start date within 7 days)

- Node D: IAM approval ticket (admin access request, approved by hiring manager)

- Edge chain:

Payroll_Record -[CONFIRMS]-> Onboarding -[AUTHORIZED_BY]-> IAM_Approval -[SUPPRESSES]-> New_Admin_Alert

If the full chain exists and is temporally consistent, suppress with confidence. If the onboarding event exists but there's no matching payroll record, or the IAM ticket was never approved, the alert escalates. The suppression context itself is suspect.

A correlation rule can't express this. It matches two events in a time window. The graph traverses four nodes across three separate systems and validates the relationships between them.

Graphs also work in the other direction, discovering attack paths you didn't know to look for.

Example: multi-hop lateral movement

A traditional SIEM sees this:

- Alert: "PowerShell execution detected on workstation."

- Analyst checks: Is this normal? Who ran it? What did it do?

- Time spent: 15 minutes per alert. Thousands of alerts per week.

Each alert is a single data point. To figure out whether this PowerShell execution is part of a lateral movement chain, the analyst has to manually pivot across multiple log sources, correlating user identity to workstation to process to network connection to destination server. Five tabs, three tools, twenty minutes.

A graph query does this in one traversal:

MATCH (u:User)-[:AUTHENTICATED_FROM]->(w:Workstation)

-[:EXECUTED]->(p:Process {name: 'powershell'})

-[:CONNECTED_TO]->(s:Server)

-[:ACCESSED]->(d:Database {classification: 'PII'})

WHERE NOT (u)-[:NORMALLY_ACCESSES]->(s)

RETURN u, w, p, s, d

This is a 4-hop path: User → Workstation → PowerShell → Server → PII Database. The query finds it in milliseconds. A correlation rule can't express this because you'd need to predefine every possible hop sequence. In a graph, you discover paths you didn't predict.

The analyst receives the full attack path as a subgraph, every node and relationship pre-correlated. They can see that this user authenticated from an unusual workstation, launched PowerShell, connected to a server they don't normally access, and touched a PII database. One screen, immediate context.

If this sounds like UEBA (User and Entity Behavior Analytics), you're not wrong. UEBA baselines user behavior and flags anomalies.

But most UEBA tools model entities as independent statistical profiles: they can tell you that this user is behaving unusually, but not that this user's unusual behavior connects to that server's unusual behavior which connects to that database's unusual access pattern.

Graph-native approaches model the relationships between entities, not the entities in isolation. The signal is the path structure, not any single node's anomaly score.

Defining "self": the topology problem

The immune system's fundamental job is distinguishing self from non-self. It builds a model of "what belongs here" and responds to deviations.

Modern immunology has complicated this picture. Polly Matzinger's Danger Model argues the immune system actually responds to danger signals rather than foreignness: your gut bacteria are "non-self" but tolerated, while tumors are "self" but attacked. For most external threats, the self/non-self framework maps well onto the baseline-vs-anomaly problem. But insider threats are the tumor case: legitimate credentials, baseline access patterns, malicious intent. A graph that only checks "does this look like self?" will miss them. It also needs danger signals, like unusual data volumes, abnormal access timing, or exfiltration patterns, even from entities that look like they belong.

In network security, "self" is your baseline topology, the normal graph of communications, access patterns, and data flows.

- Self: Marketing users access email and Salesforce.

- Self: Developers access GitHub, Jira, and staging environments.

- Self: Database servers communicate with application servers on port 5432.

- Non-self: Marketing user executes PowerShell against the domain controller.

- Non-self: Database server initiates outbound connection to unknown IP.

- Non-self: Service account authenticates from a country where you have no employees.

These examples are deliberately clean. Real environments are messier. A marketing analyst might legitimately run PowerShell for a data export. A developer might access a production database during an incident.

And agentic AI is making this worse: when organizations hand AI agents tool access with delegated credentials, the agent's behavior is non-deterministic. A marketing user's AI assistant might end up executing PowerShell against the domain controller through a chain of tool calls nobody predicted. In the rush to deploy AI, "self" is becoming harder to define, not easier. The boundary between self and non-self is context-dependent and constantly shifting. A static rule set can't keep up. A graph can.

You cannot detect "non-self" if you haven't mapped "self."

Most organizations have never built a baseline graph. They know their assets (nodes) exist. They don't know the legitimate edges: who should talk to whom and what normal data flows look like.

That's the hardest part of the whole approach. Thousands of users, seasonal workload patterns, shadow IT, third-party integrations, constant organizational change. Building a complete baseline graph is an ongoing process, not a one-time project, and it's where most anomaly detection and UEBA initiatives quietly fail. The immune system has an advantage here: it spends years in the thymus learning "self" before the body encounters most threats. Your SOC doesn't get a childhood.

But an incomplete baseline graph is still more useful than no baseline at all. You don't need to map every edge before you start suppressing known-good patterns. Start with the loudest noise sources, build outward, and let the graph grow.

Without this map, every detection is context-free. The SIEM can only ask "Does this match a known-bad signature?" It cannot ask "Does this belong in our environment?" because it doesn't know what "our environment" looks like as a connected system.

The bottom line

Stop calling your SIEM an immune system. It's not. It's a burglar alarm with a log file. Jerne understood the difference in 1974. Security operations is still catching up.

The economics follow. An unregulated SOC scales linearly: more sensors, more alerts, more analysts, more cost. Spending $500K on another detection tool when you lack correlation infrastructure is treating autoimmune disease by injecting more immune cells.

Detection has diminishing returns. Regulation has increasing returns: each new suppression edge or baseline relationship makes every connected node more context-rich. Noise drops across the whole graph.

The jump that matters is from collection to correlation to cognition. Connect events into a graph. Add suppression and amplification loops. Let the graph learn from analyst decisions.

A mature SOC isn't one that catches every threat. It's one that doesn't die of a fever trying to fight them.

This article was originally published on Medium